This content was originally published by the Longmont Observer and is licensed under a Creative Commons license.

Anyone who’s ever done math homework or helped someone else do math homework has probably wondered “What is the point of this?” I generally follow that up with a rant, “There is absolutely no earthly reason for people to divide fractions!” Finally rationalizing to myself “There is less reason for being able to tell how many cookies some child got in a made-up story problem. In real life we know one kid got completely shafted, another is allergic to gluten and either way, the parents in charge got hauled into custody by the Department of Children and Family Services.”

Consider though, that there is an important reason to learn math and that is because one day, if you’re lucky, you will be called on to assist your child with their pointless math homework. You’ll need to be prepared because they can smell your fear. If they didn’t already presume you to be an idiot by virtue of being a parent, any hesitation on your part to dive straight into the business of bits and sticks will earn their mistrust of your abilities.

That’s not true. Regardless of what you do, they’ll think you’re feeble-minded and won’t hesitate, after asking for your help, to declare emphatically that you’re doing it wrong, you don’t know what you’re talking about, “The teacher TOLD us 4 + 5 is 10! She wrote it on the BOARD!” At which point you lose. The Board always has the final word. It’s too late, anyway. Tears ensue and people stick out their tongues and slam doors. It’s childish, I know, but I still find it incredibly cathartic.

Technology, then, since we have it, seems a natural fit for the school experience in general, and an even better fit for the after-class drudgery owned by teachers and homework nightmares faced by parents. Online class portals with posted assignments and grades provide an all-encompassing continuum of communication - everyone knows their role in getting that sixth grader off to Harvard.

For students, it’s an incredible opportunity for them to finally employ technology in a purposeful way. Right. And I drink wine for the antioxidants. Anyhow, many schools began implementing the use of shared computers and tablets in the library and later in classrooms. In the St. Vrain Valley School District, our children are fortunate enough to have their own iPads assigned to them every year from sixth grade until high school graduation.

Parents are also fortunate, IF they have space to wedge one more hack-stumping, rascal-baffling p4ssw0rd#! into their standing-room-only brains. Because inherent to all of it - teachers’ class blogs, administrative portals, online fee payments and sports team messaging networks - is security. What is 100% secure here is my kid’s academic performance. I can’t hack this confounded system to save my life and I have passwords - 87 of them. By the time I get access, this guy will either be landing people on the moon or cross-breeding ferrets on a farm in Wyoming and I will have missed the entire digital experience! Meanwhile, we continue with old fashioned protocol whereby I ask my child how he did on a test. He mumbles something, probably about a hover board, and I tell him to keep up the good work.

I’d feared a bit that all this online business would make me redundant, that harping and nagging – two of my favorite pastimes – would become obsolete in the face of the organized lists, schedules, assignments and deadlines now available at the swipe of a finger. Thankfully, though, we’re only a couple months in, and I am relieved to say that pestering, as a hobby, does still have currency. The only difference is the excuses fired back. Instead of my childhood go-to, “I left my book at school,” we now have “I’m waiting for my iPad to charge.”

With the introduction of personal technology like the iPad, we parents might have rejoiced that the headache of homework wouldn’t be as severe as we remembered from our own youth, or, as painful as we’d suffered up until now. Firstly, kids can take it anywhere, making any time homework time! Secondly, if they’re doing the work on a device that also allows them to delve further into the subject matter, they might be less inclined to ask mommy and daddy for help with every single equation, translation and vocabulary word. Not bloody likely.

The same children with the patience to watch a 16-minute YouTube video of a kid crushing soda cans on his forehead cannot spare the time to complete a fill-in-the-blank Spanish vocabulary exercise or a math problem requiring them to do math. “Mommy, I need help. I don’t get it.”

Like my mother did, I have my child explain what is being asked for. No sense can be made of the string of words that follow in a monotone much like a stenographer would recite the last response from the witness. “Give me ‘that thing’!” I demand. Taking the iPad in two hands I zero in on the source, and naively search for evidence of attempts already made by the child to solve the problem. There, in a font appropriate for the warning label on a fruit fly’s prescription bottle is one math problem. My squinty eyes adjust to take in the rest of the “page” to find it empty. Nothing has been written, erased, over-written, carried over, borrowed, no bits, no sticks, NOTHING.

You mean to tell me we’re doing this in our heads?! Buddy, it’s either the last four usernames and passwords - including the one for my Starbucks account - or this single math problem. Otherwise, I need paper. But first I need to see.

Trying to make the text bigger I make it disappear! The old problem is gone, a new one in its place. Now I’m the child, and I’m panicking because I’ve done something bad, but I don’t know what and in a million years I would never know how to undo it. My son catches me trying to hide the iPad under the couch cushion. Grabbing it back, he discovers that the original story problem, featuring a tailor and some square yards of fabric has been replaced by the equally irrelevant plight of a bricklayer, a length of wall and a quantity of bricks.

The child, baffled by the half-wit he’s been stuck with as his math tutor, accuses, “You TURNED it SIDEWAYS?!”

Ummm. “Did not!” seems appropriate. “I was just trying to read it…” In my head I calculate how many dozens of story problems we could have finished – on paper – in the amount of time it’s taken us to lose this one.

“You can’t turn it sideways,” he explains, “or that one will go away and you get a new one!”

Apparently.

“Fine,” I say agreeably, cheerfully. “Let’s do this one!” The suggestion was followed by the tablet once again being tilted away from my view at which point many thumbswipes were swept and at last the thing was returned to me with another problem presented in subatomic script.

“Okay,” I start when my eyes adjust, “give me the pencil, I’ll write out the equation so you can see how the whole -- ”

But there was no pencil. Not only that, but there was not so much as a grocery receipt anywhere in sight on which one might scrawl out some long division. “Where do you write all this out? I can’t do this in my head, don’t you use paper? How do you show your work?”

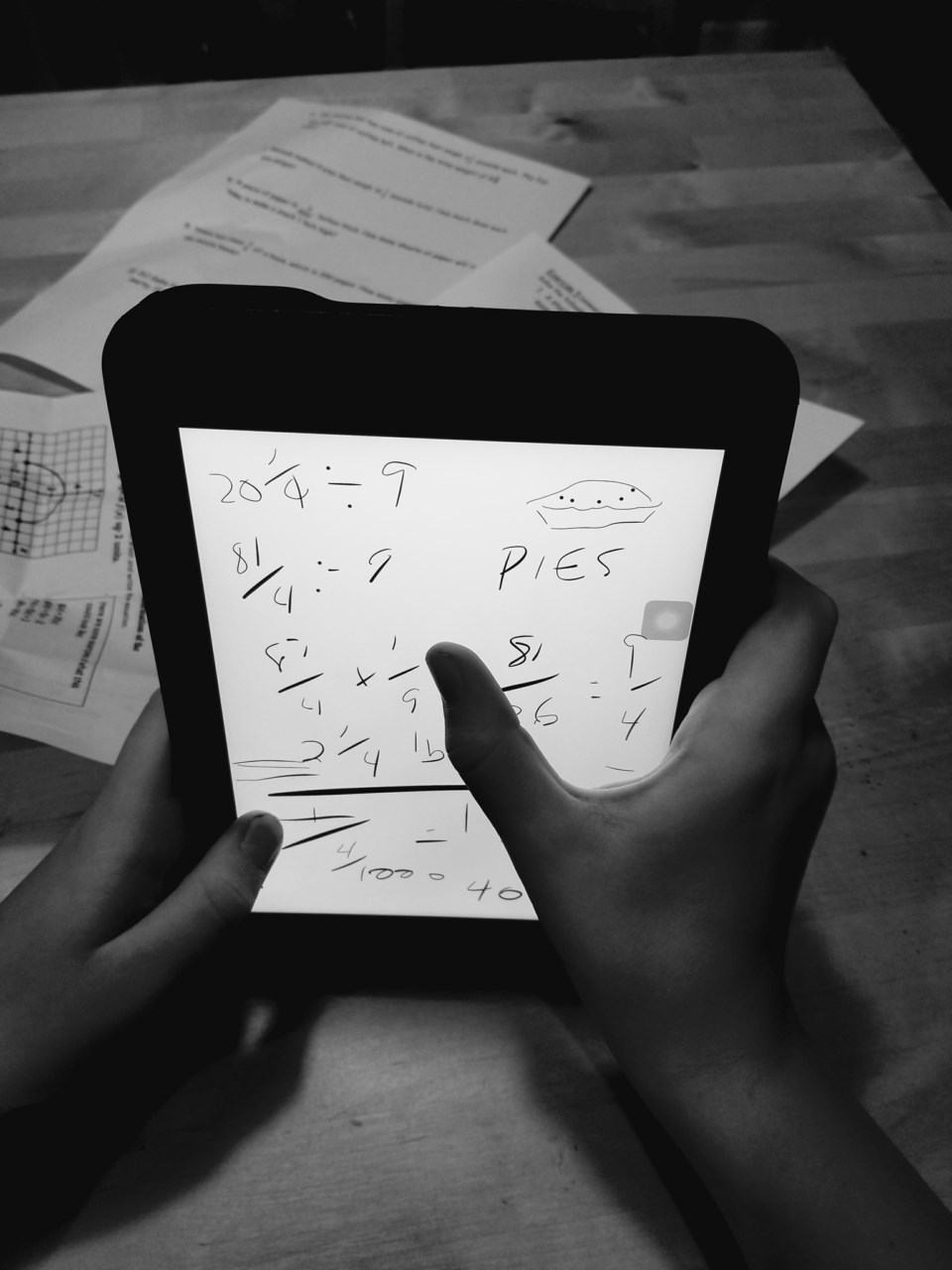

His look said, “Silly mommy.” Then he explained, “There’s a tab for writing it out.” He takes the pad back so it’s facing him again and I sit there, idle, useless, my hand twitching for a pencil. Four or maybe eight minutes and 600 thumb-swipes later, the child produces a “scratch pad.” As you might expect, writing with your fingertip soon fills the allotted space and once again, I am itching for paper and a pencil. When finally we agree on the answer, he enters it into the minuscule space, incorrectly, deleting, entering again. Hitting “submit” and waiting for the application to tell him whether or not it’s correct. I’m screaming inside, “This isn’t about math!”

My patience, having worn thin at about the point I began etch-a-sketching 3 ⅞ divided by 9/10 was further deteriorating at the prospect of eight more problems, 25 minutes each, going by recent experience, so three and a half more hours?

He resumes swipping and swiping. I sit there awaiting my cue, only this time I won’t touch the device itself, lest I obliterate another problem and 25 more minutes of my life. Waiting, my pencil is poised to illustrate a length of elevator cable measured out by floor height. This part is essential to me. As a visual learner, I’m fond of timelines, cubes and pies, objects divided into segments. If the conundrum in question involves a pizza cut into eight pieces, and Sandy eats four, not only can I calculate how many pieces the other children get, but my scratch paper will feature a fairly accurate depiction of the corpulent Sandy on the page next to the bulk of the pie.

I still can’t see what’s happening on the other side of the small screen but I’m imagining what Mona Lisa was feeling as she sat posed for her portrait with ole Leonardo on the opposite side of the canvas, his brush sweeping and gliding back and forth, he, consumed by the rhythm, muttering to himself. What might she have done if after all that he turned the easel toward her and produced ⅘?

While I’m waiting to be needed, I glance over at the enormous backpack on the chair and realize I haven’t seen a single textbook this year. Weren’t kids developing spinal disorders just a few years ago from hauling books back and forth to school that amounted to about three quarters of their body weight? Didn’t some start transporting books in suitcases or backpacks with wheels? “Where are your books?” I asked.

My son confirmed that they don’t use any. Not social studies, not English, math or biology. The iPad and the internet have made textbooks redundant! I’m feeling indignant now, that the years, pages, chapters, volumes of “yawn” I was made to endure have been deemed so irrelevant that they’ve been eliminated from the whole process. What’s to become of Mommies?

My young student pokes and swishes away and now I’m reminded of Dora the Explorer and want to shout at him, “Swiper no Swiping!” How irritating that the refrain from a show I despised should stick with me for so long. I believe the premise of Dora was that all young Americans learn Spanish? Enough of it, anyway, to follow a map to hidden treasure.

Which reminds me: treasure maps are made of paper! So are love notes, cootie catchers, spit balls and paper airplanes! I’m sure the brains behind this iPad business, with all of it’s paperless learning, think they’re onto something there! But here on the ground, where the swiping is fast and furious, I’m thinking I’ve discovered the new system’s fatal flaw. From the beginning of time, kids have been wacked with rulers for passing notes in class. For landing spitballs on the back of teacher’s head. But here we are in 2017 and the future of the paper airplane is hanging in the balance.

Yes, I’m pretty sure the most effective learning environment has always involved love notes, spitballs and paper airplanes. We can probably get by without the first two distractions, but our next study session is definitely going to involve paper airplanes. Some to fly and some for scratch paper.