This content was originally published by the Longmont Observer and is licensed under a Creative Commons license.

The Longmont police department (LPD), around the end of September of 2018, started testing the encryption of what was for decades an open police radio channel. LPD cites police officer safety, keeping personal information about domestic violence, stalking, sexual assault and child molestation victims off publicly accessible channels. Additionally, the radio silence is used to thwart criminals who were using the police radio information on police whereabouts to elude officers and commit more crime.

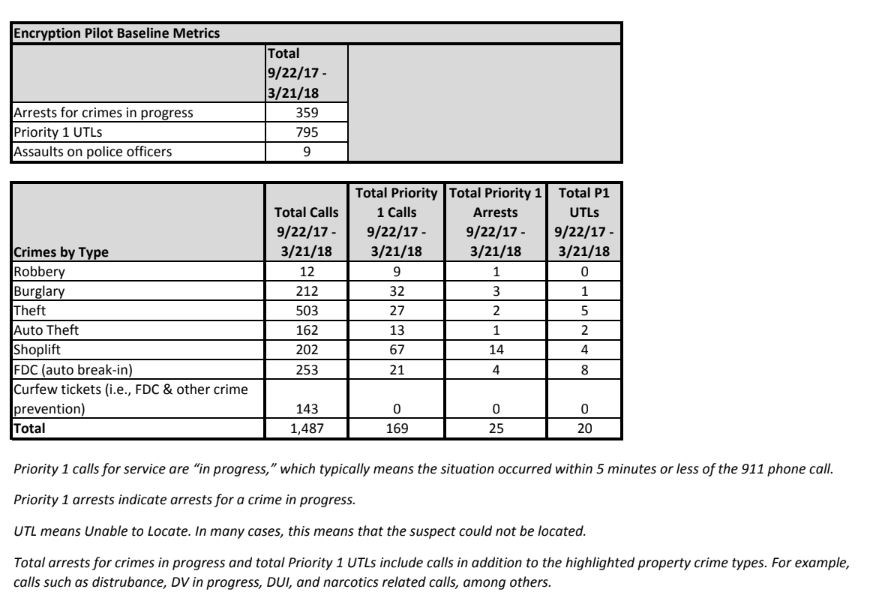

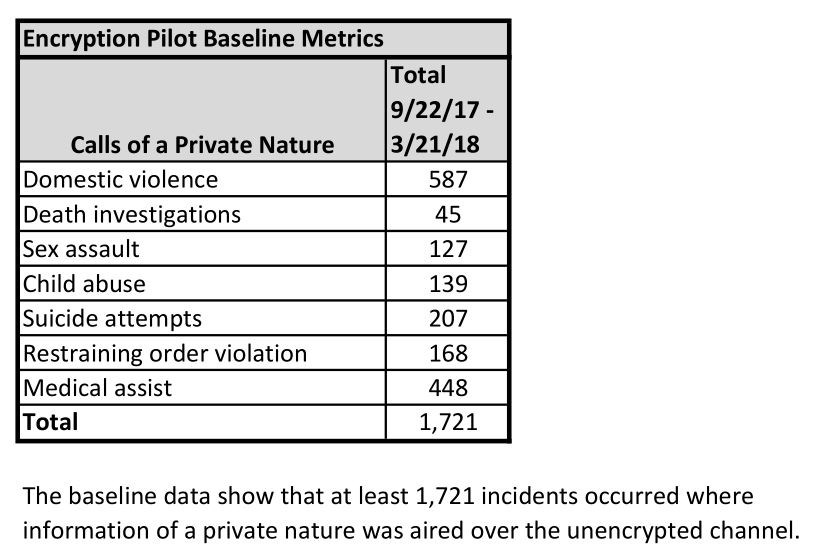

The current testing period is a pilot that will be ongoing for about 6 months and will have a set of criteria that measures the effectiveness of the program against a set of 'pre-encryption' criteria. This will then be evaluated at the end of the pilot period to see if it makes sense to keep encrypting the police radios.

There has a been some concern about transparency from a few citizens of Longmont. Gordon Pedrow, the ex-City Manager of Longmont, got up and expressed his concerns at a recent public invited to be heard session at a Longmont City Council meeting.

https://youtu.be/BDx86xC-0_E

Gordon Pedrow speaking about police radio transparency. Source: City of Longmont/Channel 8

The local Times-Call, owned by Alden Global Capital (A New York hedge fund) and based out of Boulder, also expressed concerns in an editorial about being able to find and track "breaking news" as it happens without access to these open channels.

In addition, several media groups in Colorado, the Colorado Broadcasters Association, the Colorado Freedom of Information Coalition and the Colorado Press Association, are looking at ways to address the issue. The press association CEO, Jill Farschman, said encryption "is disabling our members from being able to provide timely breaking news, which our public expects to receive."

There was also concern on the political side. Republican State Representative, Kevin Van Winkle of District 43, introduced legislation titled No Encryption Of Dispatch Radio Communications - HB18-1061 during the 2018 session where it died in the House Committee on State, Veterans & Military Affairs.

On the other side of the issue, these open channels have been a concern for local police officers for years, according to Public Safety Chief Mike Butler, more so recently.

According to Butler, "many, many more citizens have expressed support and understood the reasons why [we are piloting encryption]. We have not heard anything [negative] from anyone except those who were listening to our radio and wanting to commit crimes."

In a communication with the Longmont City Council, Chief Butler said:

"In the last part of September, Longmont police moved dispatch services to an encrypted channel. This operational modification was precipitated by a very unsafe and dangerous set of circumstances encountered by our officers."

He then went on to describe the circumstance:

"Our officers were recently 'set up' by people who simultaneously were also making death threats to our officers. The 'set-up' was intended to ambush our police officers. Fortunately, we were able to detect what was happening and responded accordingly. One of the potential assailants called dispatch complaining that they could not hear our radio traffic and asked where the police were. The threats toward police continue from these same people."

He also explained that "Police officers have been concerned for years that those who commit crimes listen to our radio traffic to determine our specific location in the community. They listen to determine when we are dispatched to crimes in progress and determine where we are at as we begin our response to that particular call for service. We've heard time and time again from individuals we were seeking on warrants or who we arrested, that they monitored a scanner and would listen for our whereabouts. In the meantime, they would continue illegal activities like car break-ins, burglary, theft, and commit acts of graffiti and vandalism. We have been made aware time and time again that people calculate our response times via scanners and can time their criminal actions in accordance with our capacity to respond."

Chief Butler gave several specific examples to the city council showing how not encrypting radio traffic had become an issue for the police department. A few of these examples are as follows:

"A robber armed with a .45 automatic warned his victim at a local business that if the police were called, he would hear it on his scanner and would come back and shoot the victim."

"Dispatched calls for service involving domestic violence, sexual assault, child molestation and other like calls almost always include names of victims, ages, and addresses of victims. We also air personal information about kids who are potential suspects in crimes. All of this information is protected information and not for public dissemination. It is imperative that we are able to discuss this type of information over the air."

"According to our domestic violence investigators, cases involving domestic violence and stalking include suspects who listen to our radio traffic to determine where we are at prior to assaulting their victims. Or they hear over our radios where their victims are currently located (which is supposed to be confidential)."

"There was another case in which multiple suspects, who we eventually arrested, were using our radio channel to time their car break-ins, burglaries and auto thefts. They later admitted that they knew where the police were and how long they had to victimize people's houses and cars."

"Our intelligence revealed that there are conversations on social media from suspects committing crimes in our community discussing concerns that they can no longer access our radio channels".

Butler also addressed the issue of transparency of information by saying "with respect to transparency of information, we have a digital connection with our local media in which every call for service, every reported crime, every arrest, every accident and every incident in which we make a report automatically migrates to the databases of the Times-Call and to the Longmont Observer every 24 hours. In the past, we've extended an invitation to our local media to join us and to have access to any non-confidential aspect of our operations - unedited. That invitation still stands."

The encryption of various police and safety agencies is a common practice in Colorado. There are, currently, 41 various agencies in the State of Colorado that encrypt their radios. This is the complete list (provided by the Longmont Public Safety Group):

The Longmont Police Department is very active in developing partnerships and enacting programs with the community to ensure that information is disseminated and available at many different levels. At last count, 113 different programs and partnerships were in place to ensure community connections and transparency between police and the residents they serve. A complete list is below:

We here at the Longmont Observer are always concerned about government transparency and we asked Chief Butler about how local media can keep in the loop, especially concerning breaking news. His response was, "We are still evaluating the utilization of radios by our media. There may be a cost to the Longmont Observer of approximately $300 for a radio."

Butler isn't making any promises to give the media police radios yet, but he has been open and honest in all of the dealings between the Longmont Observer, him and his organization.

Assuming the Longmont Police Department provide local media with working police radios that allow them to track what's happening in the community, vetted media organizations should be able to continue providing the community with real-time breaking news.

Although not as transparent as full access to anyone and everyone, this could be a fair compromise between a completely locked down encryption approach and providing a fair level of transparency and access to impartial but trusted media and other third parties.