This content was originally published by the Longmont Observer and is licensed under a Creative Commons license.

By Helen Santoro, High Country News

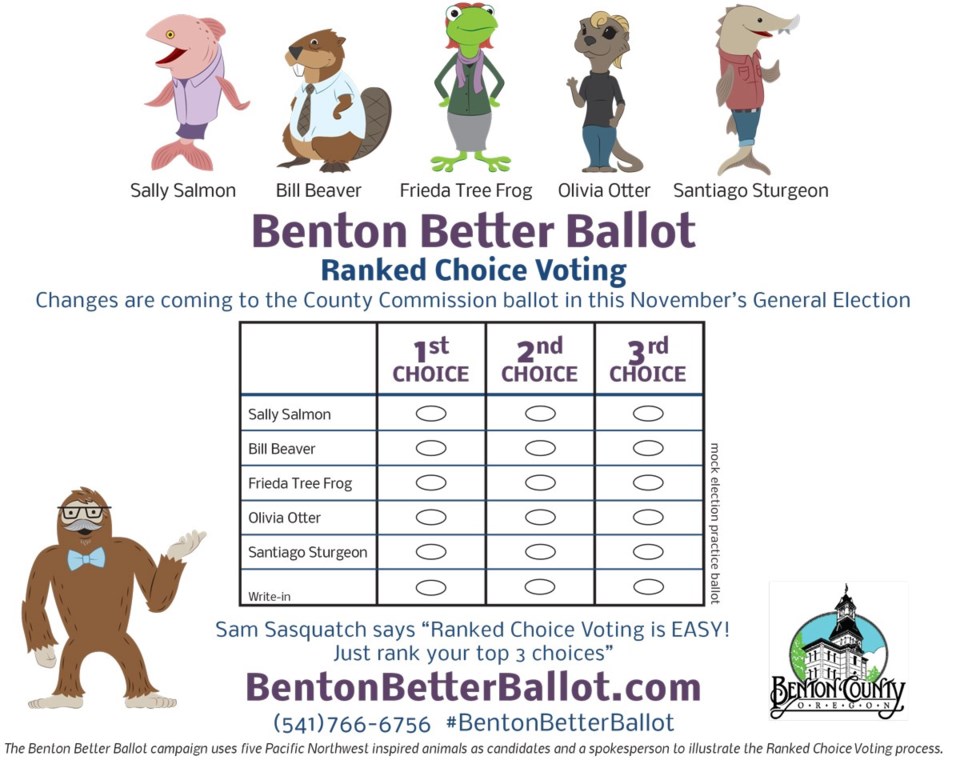

James Morales’ job is to make sure people know how to vote. Recently, that task has become harder than simply reminding them to use the right pen to fill in the bubble for their favorite candidate. That’s because Morales, the county clerk of Benton County, Oregon, is setting up an entirely new election system: ranked-choice voting, where individuals rank candidates in order of preference. This summer, Morales will help host community events at local libraries and the county fair to teach residents how to fill out the new ballots. “We want everybody to get some practice before November,” he said.

For proponents of ranked-choice voting, which passed in the county in 2016, it’s been well worth the four-year wait. “Voters aren’t stuck choosing what feels like the lesser of two evils,” said Kate Titus, executive director of Common Cause Oregon, a public interest group that promotes ranked choice. Titus and other supporters argue that the current practice of plurality voting, in which voters can only choose one candidate, limits voter choice, increases polarization and results in poor political representation.

Oregonians are not the only Americans frustrated by the current democratic process. Across the nation, counties, cities and states are turning to ranked-choice voting. Benton County voters approved it in an attempt to improve the electoral process, but political scientists are still trying to understand how the method impacts voting issues.

Benton County lies between the bustling cities of Portland and Eugene in Oregon’s verdant Willamette Valley. The majority of its residents live in Corvallis, a university town of wide tree-lined streets. “Benton County is known for its innovation and progressive change,” said Blair Bobier, a Corvallis local who campaigned for the voting measure. “People recognized the need to change our dysfunctional election system.”

Other states, including Nevada, have already implemented ranked-choice voting in some elections. This February, early voters in the Democratic caucus filled out ranked-choice ballots, providing an example of how the system works. (In-person voters attended caucuses on Election Day.) If a voter’s first-choice candidate did not receive more than 15% of the precinct’s votes and was therefore not considered “viable,” the vote would be transferred to the next highest-ranking candidate. For example, if a person’s first choice was Elizabeth Warren and Warren did not meet the viability threshold, that vote would be counted for the voter’s next highest-ranked viable candidate — Bernie Sanders, say.

Altogether, around 75,000 early ranked-choice ballots were cast, possibly contributing to the high voter turnout, which surpassed 2016’s by around 20,000 votes.

This system proved popular throughout the state. Altogether, around 75,000 early ranked-choice ballots were cast, possibly contributing to the high voter turnout, which surpassed 2016’s by around 20,000 votes. After early votes and in-person votes were counted, Sanders won a landslide victory and 46.83% of the total votes, 26 percentage points more than runner-up Joe Biden.

In Benton County, ranked-choice voting will elect county positions, including the sheriff and county commissioners. The sheriff’s race is off the ballot until 2022, but two county commission seats will be up for election this November, opening up the possibility to see ranked-choice voting in action.

Both the benefits and drawbacks are still unclear, however. Supporters say the voting system encourages more civil discourse between candidates, according to FairVote, a nonprofit organization that advocates for electoral reform. A 2016 study, which surveyed voters from 10 ranked-choice and plurality cities across a range of states, including Massachusetts, Minnesota and Washington — all of which have majority white voters — substantiated this claim. It found that voters in ranked-choice cities saw local campaigns as being less negative and divisive than those in plurality cities.

Another possible advantage — that ranked-choice voting increases voter turnout — is still up for debate. A 2016 study out of San Francisco State University found that turnout declined among Black and Asian voters in the San Francisco ranked-choice mayoral election, further exacerbating racial disparities in voter participation.

Still, the voting method is gaining ground across the country. Nine states, including Colorado and New Mexico, have implemented ranked-choice voting at state or local levels. This year, Alaska, Hawai‘i, Kansas and Wyoming plan to use it in the 2020 Democratic primaries, and Maine, which has used ranked-choice voting since 2016, will be the first state to use it in a presidential election.

Whether the new system is the best remedy for voters’ feelings of frustration remains unknown. Oregon residents have long experimented with electoral reform: The state was the first in the nation to implement vote-by-mail for all statewide elections and automatic voter registration, both of which have increased voter participation. “Oregon has a history of adapting new tools to make elections more accessible,” said Titus. “I think the people of Oregon and of this country have been working to realize the full promise of democracy.”

Helen Santoro is an editorial fellow at High Country News. Email her at [email protected] or submit a letter to the editor.

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)