Overwhelmed by the unpredictable shuffle between remote and in-person learning, scared of contracting a deadly virus, and tired of trying to make ends meet, many Colorado educators walked away from teaching during the pandemic with no intention of returning.

An already stressful job took on compounding pressures during the past three years, with teachers tending to more severe mental health struggles among students while grappling with their own. Meanwhile, political battles that found their way into classrooms and sustained community violence in schools stoked fear and frustration across the state.

But those stressors haven’t chased all teachers out of schools. Some newly minted educators have even sought out a career in a school amid the heavier workload and heightened sense of scrutiny many teachers are facing, abandoning other jobs to spend their days with kids.

The newly trained teachers enter the field as many schools struggle to find qualified educators to help them overcome shortages and retain experienced teachers, some of whom can barely find affordable housing in their school communities.

The Colorado Department of Education spelled out shortages during the 2021-22 school year, reporting that about 7,000 teaching and other staff positions referred to as special services providers — including counselors and nurses — needed to be filled for that year. Those figures represented 10% of all teaching and 16% of all service provider positions statewide.

Of more than 5,700 open teaching positions, 440 stayed unfilled during the school year and more than 1,100 were staffed through a shortage mechanism, by a staffer with an emergency license or an alternative teaching license, for example.

The Colorado Sun interviewed three Colorado teachers who pivoted to education later in life, catapulting into classrooms at a time schools are scrambling to fill staff gaps and stem the tide of outgoing teachers.

A longtime coach jumps from NFL players to middle schoolers

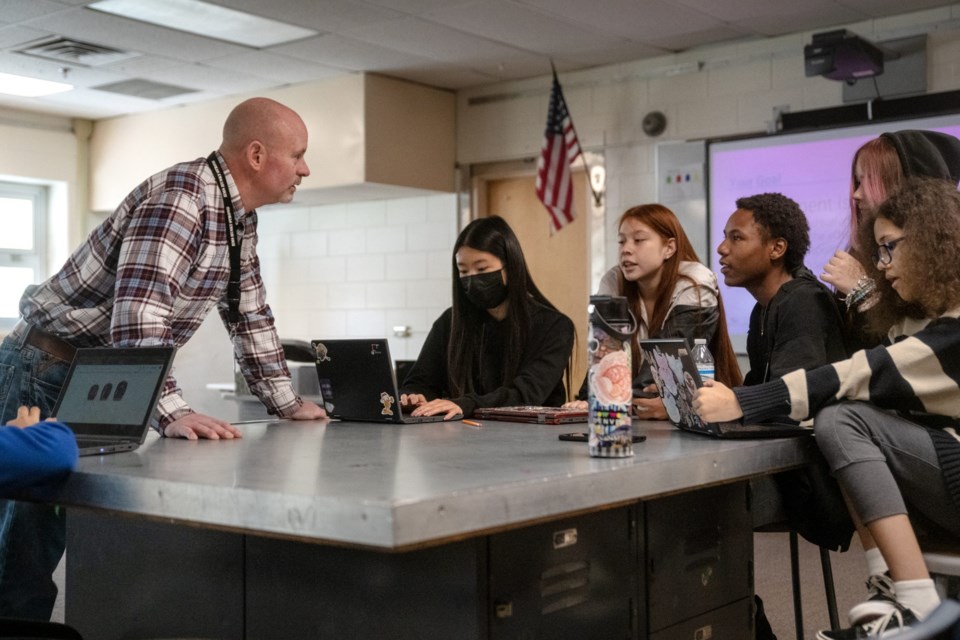

Todd Devers has a long history of teaching. But before he began instructing seventh and eighth graders about business and forensic science, his classroom on many days was a football field or weight room.

Devers coached college and professional athletes in strength and conditioning, working with the Dallas Cowboys before he moved across the country to help University of Connecticut’s football team build endurance and reach peak performance on the field.

From the outside, his career glamorous as he traveled the country with his teams and could be spotted on TV during games. And he got a lot out of training and teaching athletes while watching them progress.

But consistent stretches away from home — whether a quick weekend flying to another city for a game or an entire month for training camp, sometimes out of state — wore on him over the 15 years he spent as a strength and conditioning coach. So did holing up inside the training facility for more than 12 hours a day five to six days a week.

Devers, 48, woke up one morning and told his wife that he was going to take a sharp turn with his career and become a teacher.

Now, after pursuing a master’s degree in secondary education at the University of Northern Colorado, Devers teaches two forensic science courses to seventh graders and two introduction to business classes to eighth graders at Hamilton Middle School in Denver, where he landed for student teaching. The educator will technically wrap up his student teaching in the fall, but with an urgent need for a teacher, the school hired him on as a long-term substitute teacher. By December, he will graduate with his master’s degree in secondary education and will earn a teaching license in science.

He’s found crossovers between coaching and the classroom, including the team atmosphere between teachers and administrators and the chance to shape young lives — on and off the field and inside and outside school.

“Part of being a good coach is being able to relate to players and understand that they have stuff going on outside of the game just like these middle schoolers,” Devers said. “They have stuff going on outside of the classroom. Families, they may come from a divorced family. Dad may not be around. They have a sibling that’s struggling with something.”

But with students in front of him, Devers added, “you get to teach and watch them learn and almost forget about what’s going on in the outside world. That’s rewarding.”

The former coach has had to adjust his expectations. Whereas athletes he trained habitually worked as hard as they could, not all his students have the same feverish drive.

Still, he sticks with each one of his students, determined to make whatever impact he can on them. That, and the ability to be home with his family more, keeps the teacher coming back to the classroom, even as his salary was slashed by more than half.

“I love when I see a student or students who aren’t engaged early on, and you finally get it to click and they turn the corner and now they become that sponge and they want to learn more,” Devers said. “I love that. I love seeing that.”

This retail manager is reigniting her love of history alongside students

Most of Lena Withers’ career has been defined by stress as a veteran manager of big-box stores. Between standing on her feet during 14-hour shifts, forgoing family gatherings to cover holidays, working 20 hours straight during a blizzard and managing a Thornton Sam’s Club the day a high-speed police chase ended in the parking lot, she has learned how to cruise through all kinds of chaos.

So Withers barely flinches at the idea of teaching high schoolers at a time teaching has become an exceedingly stressful profession, particularly in history classrooms where polarizing political views have colored the lessons communities want educators to cover.

Clashes over curriculum give her all the more reason to dig her heels in while student teaching at Loveland High School, where she can tie a thread between decades of the past and today.

“I see history repeating itself,” Withers said, particularly in the past year as long-standing abortion rights have been under attack across the country, coinciding with her students’ look into the civil rights movement.

“It’s important for people to understand how things could be if we don’t protect certain rights,” she said. “People need to understand how we got to where we are, and I think they need to understand that they can have a role in it as well.”

In pivoting to teaching, Withers, 40, has traced her way back to her passion of history — the focus of her first master’s degree, which she earned at the University of Kansas. There, Withers gravitated toward teaching while working as a graduate teaching assistant and assistant instructor on the path to earning a Ph.D.

But she also worried that she would never make enough to support herself as a high school teacher.

Withers held down a part-time job at a Walmart at the time and veered away from her pursuit of a doctorate degree and was promoted while applying for other jobs. She found herself in retail management for a few years, working leadership roles at Sam’s Club and King Soopers locations throughout Colorado before stepping away at the onset of the pandemic, when her salary was cut by 25%.

Withers moved back in with her parents in Loveland and bounced through positions in office administration, management and human resources, but none of them brought her any closer to happiness.

She started to get serious about giving teaching a real try, and with her family’s financial help, she returned to school for a second master’s degree in secondary teaching and a licensure in social studies at the University of Northern Colorado. A year later, she walked in the commencement ceremony and applied for her teaching license this month. In August, after Withers completes two more classes, she will receive her degree.

Withers student taught at Greeley West High School in the fall and also filled in as a substitute teacher before moving to Loveland High School this spring. She has shadowed and taken over social studies and U.S. history classes as well as helped out with economics and psychology courses.

Her search for a full-time teaching position spans beyond Colorado as she battles the state’s high cost of living and starting salaries that fall several thousand dollars short of the pay she earned in retail management and also trail compensation in other states.

“It’s important that we support our young people today in helping them to grow and to progress, and they’re the ones that are going to be out there running things soon,” Withers said. “I hope that I can help guide them on their way to that.”

An addiction and recovery specialist takes an accidental turn into an alternative school

Hillary Higgins did not set out to teach, but once she stumbled upon an opportunity to work with kids at Red Canyon High School — an alternative school with two campuses in Eagle County — she couldn’t contemplate leaving.

The first part of Higgins’ career thrust her to the Front Range, where she became a registered psychotherapist and worked in and out of addiction, recovery and mental health, including a stint developing curriculum framed around anger management and life skills for court-ordered clients.

Higgins, 35, moved back to Vail — where she grew up — five years ago, ready for a change of scenery and eager to be near family again. A volunteer opportunity with a local nonprofit focused on stopping drunken driving connected her with Red Canyon High School by chance, planting her in the school to teach students life skills based on substance abuse prevention.

She was hooked almost instantly.

Higgins further tiptoed into teaching by taking over a consumer math class as a permanent substitute teacher at the school during the pandemic, shaking off her nerves over the idea of teaching a subject that has challenged her as someone with a learning disability. She had a chorus of educators rallying behind her who became the “catalyst” for her career in the classroom.

“They will stop and help you no matter what,” she said. “I felt so supported as a person who was teaching something I wasn’t very confident in.”

Higgins, who already had bachelor’s and master’s degrees, decided to stay on even after the educator she was filling in for came back from maternity leave. Higgins returned to school, herself, at Colorado Mountain College to complete the alternative licensure program. She finished her last class earlier this month after two years of a grueling workload, balancing full days of teaching with night classes and writing papers on weekends.

“It’s made me a much better teacher because I’m empathetic to the student perspective,” Higgins said.

She added that she would not have made it across the finish line for a job in any school besides Red Canyon High School, where fellow teachers and administrators have motivated her every step of the way, even practicing exam questions for her licensure test with her.

She understands why teachers struggle to stay in education after she took a pay cut and has worked a second job at a ski and snowboard shop owned by her parents. But Higgins still sees herself supporting students who have more significant learning needs long term, particularly since she gets to teach them an array of psychology and sociology classes, including the psychology of reality TV and fashion psychology.

She has found a family in the students she nurtures and the educators who have believed in her, and the sense of purpose that grew from her days of subbing has stuck, leading her to a career she never saw coming.

“I felt like I had so much purpose being here,” Higgins said. “I really felt it was kind of a crazy thing that happened. I loved it.”

The Colorado Sun is a reader-supported news organization dedicated to covering the people, places and policies that matter in Colorado. Read more, sign up for free newsletters and subscribe at coloradosun.com.