When Jessica May was 11, her family fostered a baby who’d been severely neglected and didn’t make a sound.

But May’s mother had a plan to get Baby Isabella cooing, babbling, and laughing just like a typical 1-year-old. The whole family lavished her with attention, and eventually, the little girl caught up on every milestone.

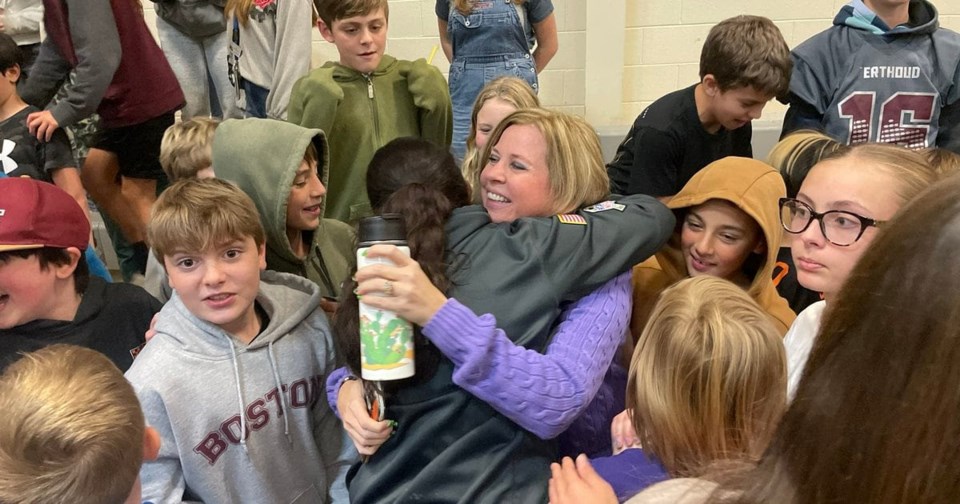

May, who is now a family and consumer sciences teacher at Turner Middle School in Berthoud, Colorado, said her experience with Isabella encapsulates what she loves about her job. These days, she helps students find their voices as they traverse the rocky road from childhood to adolescence.

All her students are her own “Baby Isabellas,” said May, who teaches lessons on everything from child development to making a budget and doing laundry.

May, who was recently named Colorado’s 2024 Teacher of the Year, talked with Chalkbeat about growing up with nearly 200 foster siblings, how she helped students cope with a classmate’s death, and what she leads with when she speaks with parents.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

No. I grew up wanting to hang out with all my teachers. I also gave assignments to my dolls and stuffed animals and graded them while they were at recess. The profession simply chose me at a young age.

How did your own school experience influence your approach to teaching?

I always loved school and had an innate longing to know my teachers on a personal level by keeping in touch with them. Growing up, I consistently asked them questions about teaching, searching for advice in order to figure out who I wanted to be as a teacher.

In fact, I still communicate with many of them. My first grade teacher just sent me a congratulations card the other day for my Teacher of the Year award. During my first year of teaching, I was paired with my former junior high school teacher, and now we are best friends!

You’ve mentioned that you like to tell students stories to connect lessons with the real world. Can you give an example?

My mom was a lifelong foster parent, starting when I was 3 years old. By the time I graduated from the University of Northern Colorado, I had 189 foster brothers and sisters. In that time, I learned a lot from my mom about kids with trauma. One of the stories I tell my students is the story about Baby Isabella.

When I was 11 years old, my mom told me we were getting a 12-month-old baby girl, but that she was the size of a 6-month-old. She explained that Isabella had learned early that when she cried, no one would respond or come to her aid — not to change her diaper, not to feed her, not to hold her. Because of this, she learned to stop crying. Therefore, she didn’t coo or babble, she couldn’t lift up her head, she couldn’t roll over, and she definitely didn’t crawl or walk.

Our job, my mom told me and my older sister, was to teach her how to cry again. The plan was to continually hold Isabella during the day and so my mom, sister, and I traded off while we went about our daily lives at home. My mom reminded us to talk to her in “motherese,” make eye contact when we spoke to her, kiss her cheeks, and sing to her. We did this for two weeks straight.

Then my mom told us “Step 2.” Every time we put Isabella down and she made any type of noise, we were to pick her up. We did this over and over until she finally realized that every time she made a peep, someone would interact with her. She started to coo and babble, she started to gain weight, she could lift up her head, and roll, and army crawl; she’d giggle and smile and squeal. By the time she was adopted at 18 months, Isabella had caught up to all the milestones of the average 18-month-old.

I explain the connection of this story to my students because they are stuck between being a little elementary kid and a young adult in high school. People, including their families, think they don’t want hugs anymore, that they don’t want to talk or play family board games, and that they want to be left alone. But that’s not accurate. They want to feel seen, heard, and talked to about life.

The reason I was meant to teach middle school and why I love it so much is because I can teach them how to “cry” again — to find their own voice, and tell others what they want and need.

Tell us about a favorite lesson to teach. Where did the idea come from?

A few years back, I had a seventh grade student with whom I had a close relationship. I dedicated several hours each week to helping him access content and overcome challenges he faced at home and in his social interactions at school. He tragically took his own life during the school year.

The loss of the student weighed heavily on my heart as he was the first current student I had ever lost. I knew I had to take immediate action for my students. I contacted the district’s restorative justice representative and requested she co-facilitate Peace Circles for each of my classes the following day. The students desperately needed an outlet to express their emotions and engage in the grieving process with their peers.

These circles evolved into experiences that profoundly impacted everyone present. They fostered a sense of safety, belonging, healthy emotional expression, and a sense of community. My hope was to make sure my students felt love, acceptance, and peace that day ... and hopefully for a lifetime.

Tell us about a memorable time — good or bad — when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach.

I think all teachers are nervous about making phone calls home because it can go either way for us. However, I have learned when calling a parent about an issue to always start with why I enjoy their child or what strength they possess. When I start this way, the parent or guardian understands that I’m not out to get their child and I have their best interests at heart. We then have a really wonderful conversation about how I can support their student so they can become their best selves. I’m no longer a nervous wreck when calling home.

What are you reading for enjoyment?

I’m reading “Screwtape Letters” by C.S. Lewis. I’ve read this novel many times, but it continues to blow my mind. He wrote this fictional story in 1942, yet so many of the situations that Screwtape — a demon who is mentoring his nephew — talks about are actually occuring today. It’s also a good reminder to be mindful about my habits, thoughts, and actions on a daily basis.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at [email protected].

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.