In the Firehouse Art Center’s upcoming main exhibit “The Language of Landscape and Memory,” Colorado artists explore their connection to the natural world. The sculptural and 2D work serves as a time capsule of our changing environment.

“The Language of Landscape and Memory,” launches with an opening reception Friday Jan. 13 from 6 - 9 p.m. at the Firehouse’s Main Gallery at 667 4th Ave. It’s on display through Feb. 5.

The three-artist show features art series from Ron Kroutel, Catherine Robinson and Meghan Wilbar. Though their work is all different in concept and medium, the three series work in tandem. Colorado’s landscape is their commonality, along with the practice of making art to relate and to remember.

Ron Kroutel

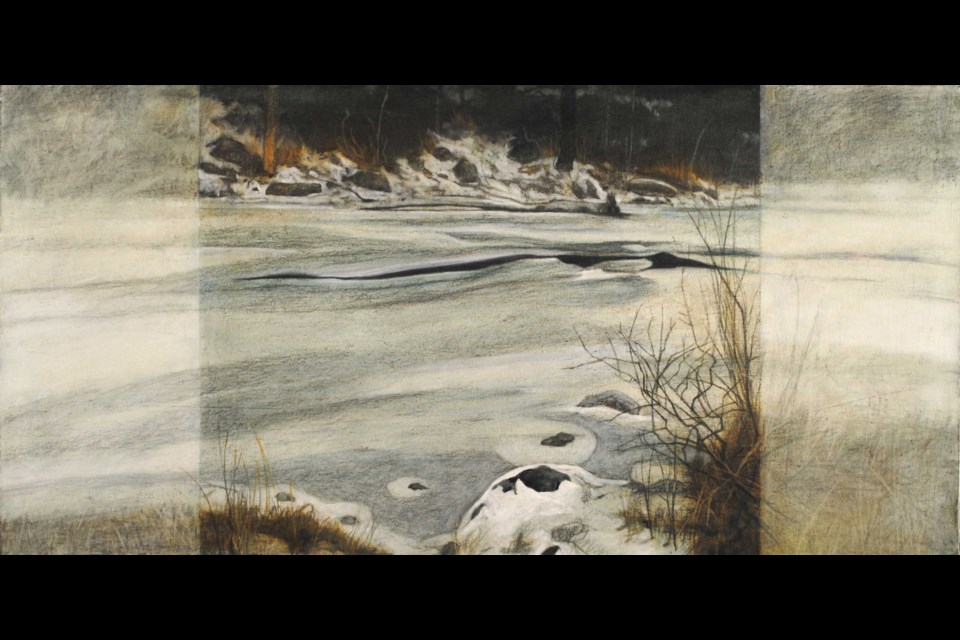

Kroutel, a Fort Collins studio artist and professor emeritus of Ohio University, is exhibiting four pieces from his charcoal and oil work, “The Glade Series.” The series is an interpreted study of the land that is under proposal for building a reservoir to be named Glade, near Fort Collins.

He relocated to Colorado five years ago. To get a grasp of his new home, Kroutel started creating charcoal illustrations of the Northern Colorado landscape. The drawings are painterly yet realistic, but Kroutel said that he references the landscape for inspiration rather than copying exactly what’s in front of him.

“Although they're not necessarily traditional landscapes, and let's say, the 19th century style or impressionist style, I use the landscape as an opportunity to discuss issues or to ask questions about things. And I also use the landscape to connect myself to my new environment,” Kroutel said. ‘It was a big transition for me. So I feel I need to be connected to my area, and I need to understand it in my own way.”

Instead of drawing the grandeur of high mountain ranges, which define Colorado’s characteristics, Kroutel wanted to look closer to home. He learned about the Northern Integrated Supply Project, or NISP — a water use project that’s been held up in permitting processing since 2004 — which plans on creating pipelines, other storage and supply infrastructure and two reservoirs with Glade being the primary. It would be built near the base of the Poudre Canyon using water diverted from the Poudre River, northwest of Kroutel’s current hometown.

He’s not sure how many drawings and paintings have come out of “The Glade Series” over the last few years. Though there are many, including drawings gifted to the Gregory Allicar Museum of Art in 2021. He is also exhibiting five paintings in the museum’s drawing collection Jan.18 through April 30 during the same time he’s showing at the Firehouse.

“The Glade Series” is not a symbol for how Kroutel stands on the NISP. He said he’s close to people on both sides. Rather it’s his way to ask questions and ponder what happens to the land he’s made countless drawings and paintings of when it’s eventually underwater.

“So [The Glade Series’] got two prongs to my investigation. One, is just to understand where I'm at on this planet and connect to it in some way in some real way that I really identify with,” Kroutel said. “And second, to come up with a subject matter, a kind of landscape, that would be interesting to people and perhaps raise questions, and involve them in that way.”

Meghan Wilbar

“The Language of Landscape and Memory” displays five multimedia paintings from landscape artist Wilbar of her hometown of Pueblo. The brown monotone pieces are crafted with matte board, paint and other materials on wood panels.

Though the multimedia collection are gallery-worth pieces, she considers the artwork on exhibit at the Firehouse as drawings or sketches, later to be a blueprint for a painting. Rather than studying landscapes with a pencil and sketch book, Wilbar tears pieces of matte board to create dimensional clouds, fences and hills.

All of these sketches are made in the front seat of her car, using a contraption she made to rest the wood panels on her steering wheel. Pieces of paper and drawing materials are at an arm's reach on a table she built in her passenger seat.

Wilbar’s drawings are a way to document the places around her hometown. But, since she takes several sessions to complete one, there’s a sense of impermanence. With every new layer of paper, is another memory of the same location over time.

“I think for me, doing kind of the process of building paper on, I do feel like I'm creating memory within the drawing itself,” Wilbar said. “I think each one of these, I drove back multiple times. So it's kind of the memory of did I want the clouds to be like that? Because, you know, they're not there anymore. So it's kind of just that moment of things being fleeting.”

Wilbar studied art around the country before moving back to Pueblo four years ago.Though she started her sketching practice during a residency in Wyoming, she refocused on her hometown, and its ties to her family.

Wilbar’s father’s side is multigenerational Southern Coloradans, dating back to when Colorado became a state in the 1870s. She often studies the places in town she’s seen change over the years, while pondering what her ancestors once saw.

“I was trying to look at places where my family has kind of been and kind of remember places where they lived,” Wilbar said. “The drawing “Bridge” is in Pueblo. That's maybe three blocks from my house, right on the Arkansas River. During the time that I was drawing it, they were tearing down the levee to make changes on it. It had previously been this whole long mural that had been on the levee, and so I went back maybe 20 times to do it. And in that time, I got to watch the construction tear away parts of this mural that had been there.”

The drawings are attached to Wilbar’s memories, but she hopes it sparks a similar connection in the people who visit the exhibit. They are familiar scenes of long road stretches, lined with utility poles, that disappear into hills and clouds painted in a monotone palette. Wilbar said she hopes they can transport viewers back in time to their own memories.

“What I hope is that it connects them to their own kind of landscape. I've had people before that, look at it and remember their own childhood or the way they felt in a certain moment,” Wilbar said. “And I think that's kind of the wonderful thing that art can do is that it means something to me, but it also means something different and personal to someone else.”

Catherine Robinson

Palm-sized handbound books inside of protective boxes by Robinson will be on display at the Firehouse. Each book is different, using torn pages from other books. The jewel and earth-toned boxes range from simple openings to complicated clamshells.

Robinson’s background is in landscape plein air painting, or painting outdoors. Though the miniature book series, called “Strata,” is more symbolic, they are still landscape art.

Moving to Colorado a decade ago, Robinson was inspired by the layers of rock, or earth stratum, visible in the state’s landscape. The rough edges of her books are painted to look like layered rock. She compares the way history is recorded in the earth, to the human history recorded in writing.

“It is a reference to the strata layers that you can see, most people in the Front Range would be most familiar with them right outside of Morrison, when you drive down I-70. You can see where they've cut through that shale and it shows all these layers” Robinsohn said. “It's like a millennia of the history of the world, history of the earth. And seeing the torn edges of a book, I was like, I wonder what would happen if I painted the edges of the book and it looked exactly like the strata. Books tell stories, the strata tells us a story.”

She refers to her “Strata” series as mnemonic devices, or a technique to trigger a memory. The boxes containing her books are accompanied with natural objects including bones and crystals, in hopes viewers will associate them with a past experience. For Robinson, the books and their boxes hold memories of where she was when she built them.

Though these small books are inside of protective cases, they are meant to be handled. She first made the boxes as a traditional way of preserving her books. But for her, she said the experience of opening the cases and flipping through the pages are just as much a part of the art as the art itself. Robinson said the fear of the books getting damaged is something she let’s go of.

“A lot of times people have an emotional reaction when they're allowed to hold and touch the book and I want people to have that and want people to experience it. Like the works are meant to have sort of a spiritual quality to them. And if you're not allowed to touch it, you definitely lose out on that,” she said. “With most artists’ books, the work isn't complete until someone can read it, and handle it and flip through it. And ironically, the artist typically isn't there for that experience so we never see the finished piece.”

The small-sized scale provides a sort of intimacy, Robinson said. Viewers have to hold it close, as if it’s something precious worthy of protection. She hopes that her art makes people think about land preservation, and how it too is something to hold dear.