Lea esta historia en español aquí.

***

After losing their jobs in March because of the coronavirus pandemic, Elvia Robles and her husband, Salvador Enriquez, struggled a bit — until things turned worse. In May, they both began to show symptoms of COVID-19, while hers improved his did not.

“The doctors told us that he was in critical condition. Instead of getting better, he was getting worse every day … They did not see him getting any better, and they didn’t think there was anything else they could do. I decided to fight until the end,” Robles said. “To soften their hearts, so they would keep fighting, so that I would fight and they would fight alongside of me, and that’s how we remained for a while.”

Enriquez was intubated at the hospital and in a coma for about a month.

“It was our wedding anniversary and he was still asleep, and the only thing I asked for was for him to be awake or to at least know he was getting a little better. (Two days later) he opened his eyes,” Robles said. “It was the most beautiful gift that could have come into my life.”

The family continues battling with the aftermath of COVID-19. The disease has left Enriquez’s left arm immobilized, he has lost some of his hair and nails, and both he and his wife are still not completely back to work. Robles has started a GoFundMe page to help pay her husband’s medical bills.

A disproportionate impact

While not all who contract COVID develop serious complications from the disease, Hispanics in Boulder County have seen a disproportionate impact on their health and livelihoods.

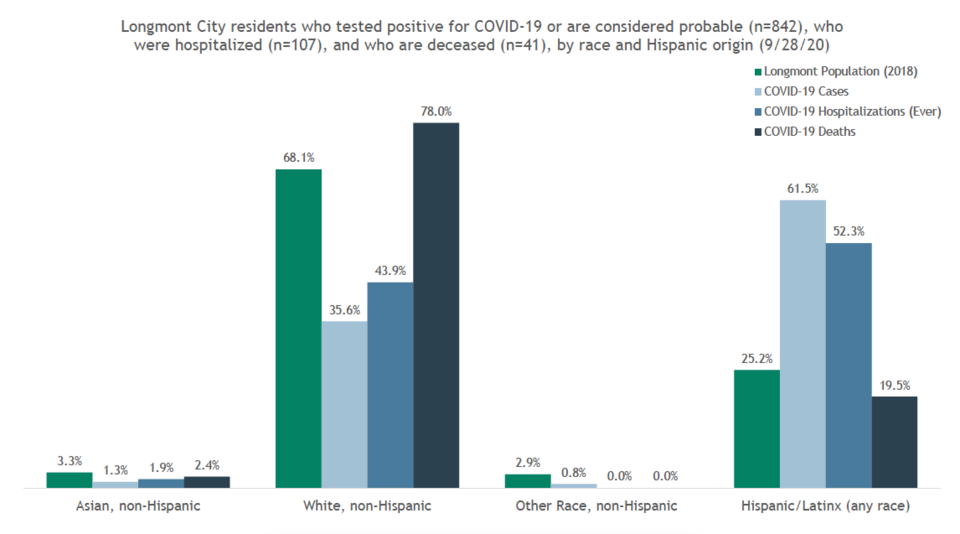

In Boulder County, as of Thursday, close to 30% of residents who tested positive for or are probable for COVID-19 were Hispanic or Latinx, according to Boulder County Public Health data. About half, 44.7%, of those hospitalized because of COVID also were members of the Latino community.

As of Sept. 28, the most recent date for which data was available, the numbers for Longmont are even more alarming, with a Latino/Hispanic population infection rate almost six times as high as the white, non-Hispanic population and even higher compared to other non-Hispanic races, according to data provided by Boulder County Public Health spokesperson Chana Goussetis.

Source: Boulder County Public Health

Source: Boulder County Public Health“Unfortunately, we’re still seeing COVID-19 in the Latinx community at greater levels than among other community members, proportionately,” said Goussetis.

Such disproportionate impact is in step with national trends.

NBC News last month, quoting Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, reported that hospitalizations among Latinos as of Sept. 19 were 359 per 100,000 compared to 78 per 100,000 among whites. Deaths related to COVID-19 were 61 per 100,000 in the Latino population compared to 40 in whites, and Latinos represented 45% of deaths of people younger than 21, according to NBC News.

Facilitator Ana Gabriela teaches an empowerment class to Longmont's ELPASO VOZ group at Roosevelt Park on Sept. 29. (Photo courtesy of ELPASO Movement)

Facilitator Ana Gabriela teaches an empowerment class to Longmont's ELPASO VOZ group at Roosevelt Park on Sept. 29. (Photo courtesy of ELPASO Movement) Inequitable access to support

Institutional barriers to preventive medical care, healthy food, safe and stable housing, quality education and transportation contribute to impact disparities, according to Boulder County Public Health.

“The problem is rooted in generations of systemic racism and inequity. Our long-term strategy is to use a racial equity lens with every decision we make in order to identify unintentional harms and culturally appropriate strategies,” Goussetis said.

Jorge de Santiago, executive director at El Centro Amistad, and his team have seen the impact up close.

According to a survey conducted in April by El Centro Amistad, out of 787 Latino individuals in Boulder County who responded, 90% have experienced inequities in areas such as housing, employment, education, economic support and access to health care. Specifically, 91% shared they have lost their jobs and 71% said they did not have access to medical or preventive care.

“Out of all the families that we have helped, which are approximately 700 across the county, between 65% and 70% are undocumented families. The rest of these families are what we called nexus status, that have one person who is documented and received the (federal) stimulus check,” said de Santiago, adding that while these families see a disproportionate impact in most areas of their lives, they are hardest hit economically.

Among Latinos, the immigrant and undocumented immigrant community is the most marginalized, said Laura Soto, operations manager at Philanthropiece Foundation, who has seen those who are most scared of seeking resources.

“They are fearful of the public charge, of being reported to ICE, of government attack,” she said.

For Robles, not having a Social Security number has affected her and her husband's chances of regaining employment.

“It impacted us economically, like you have no idea, because we lost our house, we lost everything. We had some savings and we were left with nothing when the pandemic started,” she said, adding she only is getting 10 to 15 hours a week at her cleaning service job.

Latino families across the community have seen their lives impacted to different degrees by COVID-19 and the pandemic.

Experiences widely vary, but the lives of most have been touched by the health and economic crises in one way or another, according to Carolina Neri, Longmont community organizer at ELPASO, an organization committed to the Latino parent voice. ELPASO is an acronym for Engaged Latino Parents Advancing Student Outcomes.

For Monica Pulido and her family, there was much uncertainty when her husband, who works in the construction industry, saw his job halted for about a month.

“Many people do not recover fully or are able to go on with their lives, I don’t know why this happens. It’s something to be concerned about because we have to continue with our lives as normal. I think I can get sick just going out to get my groceries or my husband when he goes out to work,” said Pulido, adding that her husband’s nephew, who was gravely ill with COVID-19, continues to battle with the aftermath of the disease and whose uncle-in-law has died from the virus.

While varied, what many of stories have in common is the fear and hesitancy of Latino families to access available resources, Soto said.

“I continue to hear the community say that they are fearful to ask for resources, report medical conditions. There are a number of people who have been sick and are really suffering not having their basic needs met, have not accessed all the resources they have available. They are still there, sick and isolated because they are fearful to come forth,” she said.

Solution years in the making

For the past few decades, leaders in the Latino community have advocated for greater equity and better representation, according to Guillermo Rivera-Estrada, Cultural Brokers Resilience Program and Suma coordinator at Boulder County Community Services. Through informal and formal networks, within and outside of community and government agencies, leaders and cultural brokers have pushed solutions, he said.

Efforts such as Resiliency for All, a project developed to identify barriers and “create a bridge between a vulnerable sector of our Latino population, community resources and local governments in the city of Longmont and Boulder County” in response to the 2013 floods, according to the website, as well as daily efforts of community groups have led to the strengthening and gradual formalization of relationships and networks aiding the Latino, monolingual Spanish-speaking and immigrant population, Estrada-Rivera said.

Soto said, “(Latino-led organizations) have direct connection, ongoing connection (with the immigrant community) and people now know that this is the place of trust. They have the immigrant community trust. They have been there for the community during this time and for years before. They have been recognized by the community itself as the trustworthy organizations that will give them the answers to their questions and that will guide them.”

Organizations such as El Comite de Longmont, El Centro Amistad, ELPASO and, most recently, Intercambio, among other formal and informal groups, have served as a link between agencies and the Latino community, according to Soto.

“The way we reached them was through the Latinx-led nonprofits. It was thanks to their work on the ground and to their outreach and direct relationship that we were able to distribute cash assistance into the hands of those not getting any assistance whatsoever from federal aid,” she said, adding that through this network and the support of county nonprofits, Philanthropiece was able to reach over 200 undocumented families who received $500 in emergency cash.

What the crises resulting from COVID has revealed is systems unable to engage everyone, de Santiago said.

“We are talking about government, medical institutions and even nonprofit organizations, which are really not prepared yet to give access and equality to our community in situations such as this,” he said.

De Santiago acknowledges that nonprofit organizations that provide for people’s basic needs, which primarily include the Emergency Family Assistance Association, OUR Center and Sister Carmen, have been key in mitigating the impacts of the pandemic but their support is limited.

“If it wasn’t because of these organizations, our community would be in the street and I am very grateful for that. But at the same time, their capacity has limits,” he said.

Among the top barriers is access to government funds because of legal status, according to de Santiago. In addition, Boulder County has had to face a blindspot when it comes to serving the Latino community that requires more responsive and culturally adept services, he said.

El Comite de Longmont case manager Rosy Quiroz helps clients in person at the organization's office. (Photo courtesy of El Comite of Longmont)

El Comite de Longmont case manager Rosy Quiroz helps clients in person at the organization's office. (Photo courtesy of El Comite of Longmont) “Institutions, elected officials, big organizations led by people who are not of color, who are white, need to understand that if you are providing a service or assistance to people of color, you need to have people of color or from that same culture providing the services,” said de Santiago. “Being bilingual is not enough.”

The Community Foundation serving Boulder County provided $15,000 to El Centro Amistad, which with the help of EFAA, was able to support close to 150 families during the height of the pandemic, de Santiago said.

What seems to be a determining factor for reaching the Latino community in times of crisis is having the trust of the community.

“People come to El Comité because they trust in us. If they have questions about the police, if they have things related to domestic violence, they come. We then talk with these agencies and help the people,” said Donna Lovato, El Comite executive director, adding it has been one of the few organizations offering services in person. “They feel more comfortable being able to come to the office and speak face to face,” she said.

El Comite has received about $45,000 combined from the Knight and Colorado Health foundations, as well as other funding from county, city and philanthropic agencies, most of which has gone directly to clients, according to Lovato.

The problem with access results not only from unfamiliarity with or fear of the system, but also is connected to a sense of pride many members of the Latino community experience in relation to asking for help, said Tere Garcia, executive director of ELPASO.

“The situation when one comes from another country is that in other countries these agencies do not exist. People in this community are ashamed to ask for help, but here if you don’t, you die. Little by little, parents have been learning to go. They don’t want to beg, but we tell them it’s not about begging but insisting (for support),” she said.

Still much to be done but there is hope

The complexity of the solution likens the complexity of the problem, and there are still many pieces of the puzzle to be improved, especially surrounding information sharing and access to resources, Estrada-Rivera said.

“Building trust and relationships is needed for people to seek and access services,” he said.

What has become evident is that as they experience unprecedented need and encounter culturally responsive systems and a helping hand, Latinos seem more willing to ask for support.

“What happens is that you help a small group of people and the word spreads from that, this is especially true with this population. People tell their neighbors and friends, and now everyone knows,” said Martin Martinez, Boulder County Housing and Human Services bilingual family support specialist.

Cultural brokers have served a key role in connecting people to available resources, as is the experience of Martinez, a cultural broker himself, whose job goes well beyond the 9-to-5 shift.

A trend he said he has seen is people connecting with him individually as opposed to through the department. “I get a lot of phone texts. People tell me ‘(so-and-so) gave me your phone number and said you can help me with rent.’ I have been noticing that as a trend a lot,” he said. “In order for me to do something, I have to believe in (it). I am going to do this extra work because I want to help the community.”

The COVID crisis has revealed the importance of collaboration across sectors in effectively providing services, according to de Santiago. It also has helped highlight the strengths and resiliency of the community.

ELPASO’s Neri said, “One way or another we have been taking care of those who are sick and aren’t able to leave home, by bringing food, medicine, on top of the other kinds of support. These are the kinds of things that makes this group... and the community so strong, that we take care of each other in that way, with families and neighbors supporting each other.”

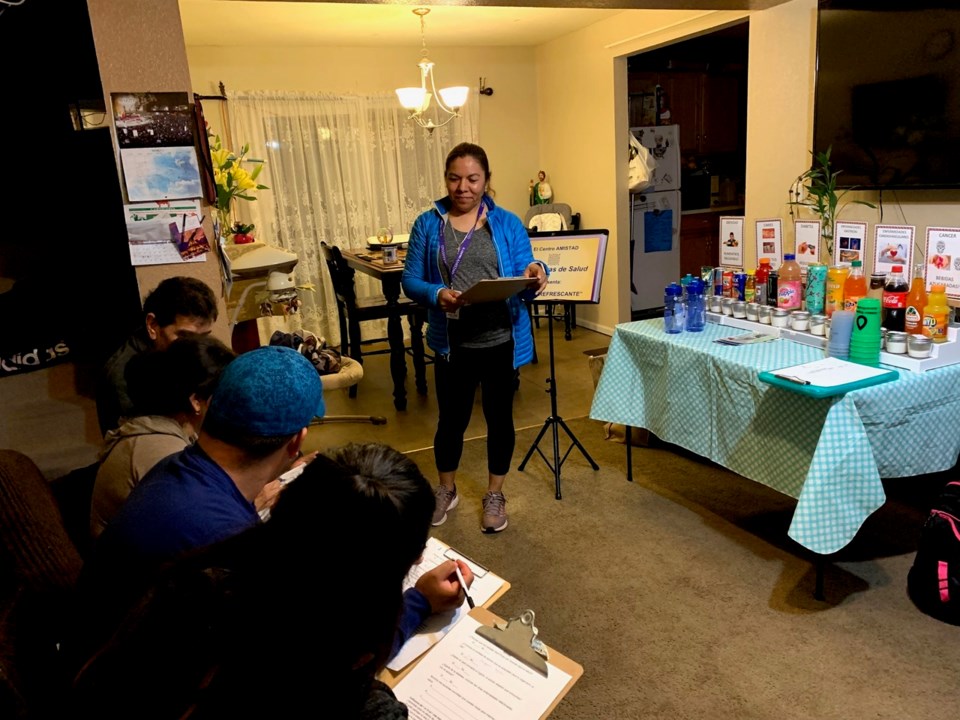

Centro Amistad Health Promotora, Lupita Jaime, giving a presentation on sugary drinks at a client's home before the pandemic started. (Photo courtesy of El Centro Amistad)

Centro Amistad Health Promotora, Lupita Jaime, giving a presentation on sugary drinks at a client's home before the pandemic started. (Photo courtesy of El Centro Amistad)