Michelle Larson often sat with fading COVID-19 patients, holding their hands and talking softly to them. Larson knew her voice was the last sound many COVID victims heard before they slowly slipped away.

As a veteran intensive care unit nurse, Larson knows medicine and technical knowledge is important to saving lives. She and other ICU nurses also know the final human touch is just as vital for frightened patients cut off from friends and family during COVID restrictions.

“We would stay in the room with them and hold their hands and talk to them until they passed away,” the 57-year-old Larson said. “That's what I would want for my loved one. We did everything we could to make them comfortable and to let their families know someone was there with them.”

“It is difficult, it is still difficult,”Larson said, who began work at Longmont’s UCHealth Longs Peak Hospital when it opened in 2017. She spent 18 prior years at Longmont United Hospital’s ICU.

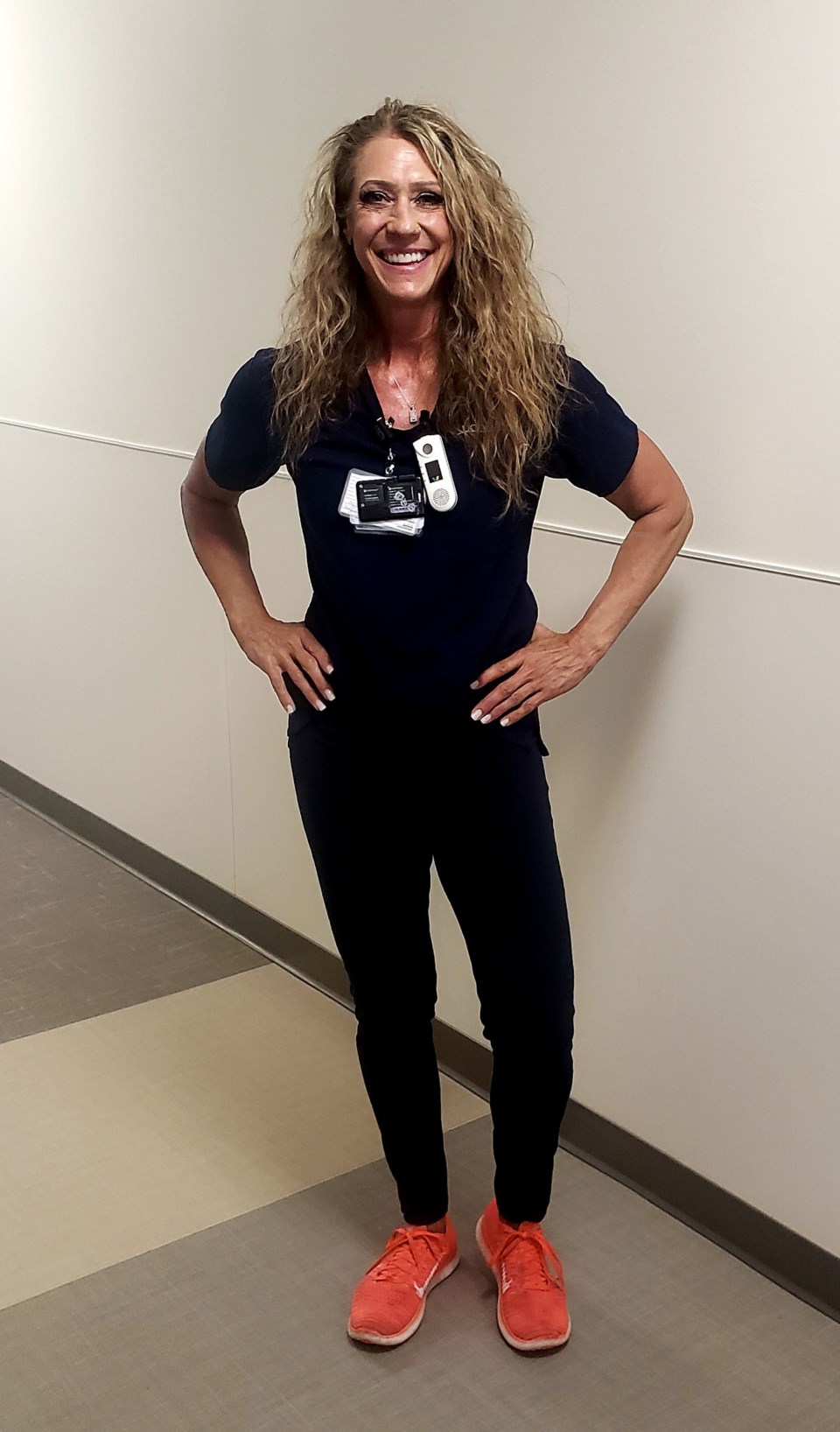

Larson’s efforts in nursing are highlighted because May 6- May 12 is designated “National Nurses Week, ” which ends on Florence Nightingale’s birthday. And while the work of nurses is being celebrated nationwide, the COVID-19 pandemic is taking its toll on the profession.

Business Insider reports, that in a Trusted Health online survey of over 1,000 travel nurses, 67% said they did not think the healthcare system was prioritizing nurses’ mental health and well-being. Of the 46% of respondents who said they felt less committed to nursing, almost half said they were considering leaving the profession, and 25% said they were looking for a job outside of nursing or planning to retire.

Larson said she’s seen the toll the COVID-19 pandemic took on her profession. Some have left nursing and others are thinking about it. The 12-hour shifts that often stretched well past the time to go home and the uncertainty about the virus, make them rethink their lives in nursing, she said.

“It was just too much for them,” Larson said. “They didn’t want to put their families at risk. They didn't think it was worth it.”

Larson’s work in hospitals seems a far cry from her previous career as a restaurant and nightclub manager in Chicago and Phoenix. Larson said she was drawn to nursing because she wanted to do something more meaningful with her life.

“Seeing the nurses taking care of my grandparents at the end of their lives … it really made an impression on me, they were just so wonderful with them,” Larson said. “I just wanted to do something with a little more meaning.”

She admits the first few months of COVID-19 were scary. No one exactly understood the pandemic and how best to control it. It also stung Larson that she couldn’t see her granddaughter for fear she would spread the virus.

“It hurt, it really was heartbreaking,” she said.

Staff cohesion, aid from outside departments and looking out for each other’s mental and physical health, helped the ICU maintain course, Larson said.

There were also good days among the bad, she said. “When you see people come back, and we hear doctors talk about patients and how good they looked, that makes us feel great,” Larson said. “What we did made a difference.”