LCJP’s partnership with the Longmont Police Department has made Longmont one of the only cities in America with a robust restorative justice program that serves juveniles and adults.

Longmont Community Justice Partnership, or LCJP, is a nonprofit organization that uses restorative practices to build community and give people an opportunity to heal, according to its website.

Beverly Title devoted her live to peace and restorative justice. (courtesy photo)

Beverly Title devoted her live to peace and restorative justice. (courtesy photo)

LCJP began 25 years ago when Dr. Beverly Title, a 50-year-old Longmont resident, decided to devote her life to peace.

Her efforts began by forming a nonprofit organization called Teaching Peace with colleague Lana Leonard, a St. Vrain Valley School teacher and multicultural storyteller.

Mike Butler, former Longmont Public Safety Chief and an early supporter of Teaching Peace, said the program was devoted to helping troubled youths gain an education and make something of themselves by teaching them to be responsible for their actions. This was done through an alternative school, in coordination with but outside of the St. Vrain Valley School district, called Clearview.

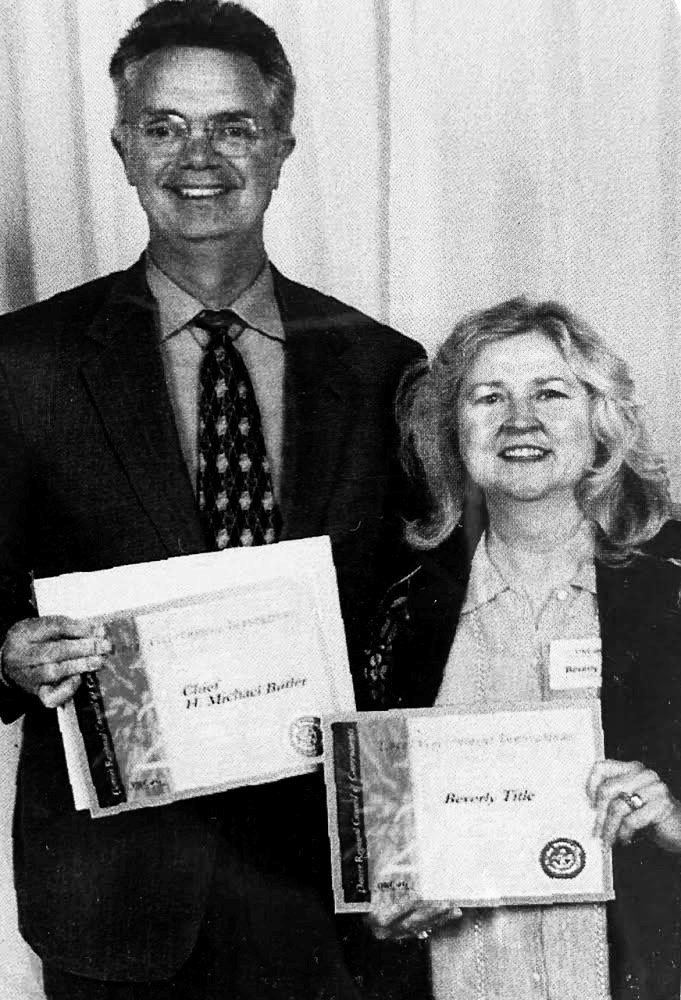

Mike Butler and Beverly Title receiving an award for work on restorative justice in 2000.

Mike Butler and Beverly Title receiving an award for work on restorative justice in 2000.

Title’s experience as a former teacher on special assignment with the St. Vrain Valley School District had provided her with the tools and skills she needed to coordinate the program. ““The original focus for their work centered around no-bullying, school violence prevention, and multicultural storytelling, reflecting the expertise of the founders,” said Summer Deaton, Title’s daughter and former LCJP director of operations and training.

Title was determined to give students enrolled in Clearview a second chance in life by holding them accountable for their actions.

“She recognized that these young people were beautiful spirits caught up in challenging life circumstances which they often responded to violently with defiant and disruptive behavior,” said Deaton. “Her students taught her that punishment is often internalized as another form of violence done to them, leaving them feeling entitled to ‘return the favor.’”

“Beverly realized that discipline was necessary and that punishment would not be effective. At the same time, she knew that leniency was not the answer because she believed that one of the kindest things she could do for her students was to hold them accountable at the lowest level so they could fix the issue before it caused even bigger problems” Deaton said.

Bringing restorative justice to Longmont

Title attended a conference in 1996 to explore how best to serve the youth she was working with when she heard the words ‘restorative justice’ for the first time. Restorative justice is the rehabilitation of offenders through reconciliation with their victims and the community.

After hearing these words, Title knew what she needed to do next.

“Beverly was a pioneer in the field of restorative justice, and the early days of LCJP were all about building collaborative relationships and training volunteers,” Deaton said.

Title developed the “5 R’s Framework” – relationships, respects, responsibility, repair and reintegration – that became the foundation of LCJP’s work.

“Longmont had always been a community of collaboration, and she knew that she’d need broad support to get restorative justice off the ground,” Deaton said. “By the end of the week, she had collected support and original signatures from the police chief in Longmont, the local school district superintendent, the municipal judge, the probation department and the director of a school for expelled students. All agreed to participate and the Longmont Community Justice Partnership was formed.”

Although Title had the support of these organizations, it took a while to get the concept implemented in the criminal justice and school systems. By 2009, with the help of dedicated community members, she had done both.

“It was a long labor of love because building partnerships within the community and with the police and with the schools was not necessarily easy because there was a new paradigm that she was creating,” said Linda Leary, an LCJP volunteer for the last 23 years.

Butler was an early adopter of restorative justice practices, after years of feeling stuck within the criminal justice system and not seeing true reform.

Butler did a study where police looked at 235 people who had been arrested in one year time for the crimes of burglary, auto burglary and vandalism, with no other crime attached. All of these crimes are felonies. Butler discovered that, on average, those 235 people had been arrested nine times prior to that year with an average of 16 charges filed against them. Butler felt like the criminal justice system had failed those 235 people.

Beyond that, Butler said that each of those crimes created more victims, victims whose voices were rarely heard. For him, adopting restorative justice was easy because it puts the victim’s voice in the forefront and allows the offender to be accountable for their actions.

“The other part of this that weighed heavily on me was that restorative justice doesn’t define someone by that one act,” Butler said. “Whereas the criminal justice system, you get arrested, you get convicted, you have a record, and that record tends to be an anchor that kind of holds you back.”

A one-of-a-kind partnership

The restorative justice practices that Title began have paved the way for a unique partnership between LCJP and the Longmont Police Department. According to Butler, Longmont is one of the only cities in America with such a robust restorative justice program.

“There are very few models of restorative justice and police partnerships like ours in the country,” said LCJP Executive Director Kathleen McGoey.

The program is set up so that the police can evaluate a case and refer the ‘responsible party’ or the person who did harm to the restorative justice program if their case fits, said Sergeant Matt Cage, an early adopter of restorative justice practices in the Longmont Police Department and LCJP police liaison.

Once referred to the program, LCJP and police work with the responsible party to make amends with the ‘harmed party’ through a conference, Leary said.

“It’s an educational experience… It’s also a humanizing experience,” McGoey said.

Cage has spent most of his career in Longmont working closely with LCJP. He remembers a time when officers only had the criminal justice system to work with and when “old-timers,” as Cage referred to them, knew the courts and didn’t buy into a new way of handling cases.

“They didn’t really buy into the program,” Cage said. “They didn’t really have or utilize other options.”

Kathleen McGoey and Longmont Police Officer work together as clients go through restorative justice program. (courtesy photo)

Kathleen McGoey and Longmont Police Officer work together as clients go through restorative justice program. (courtesy photo)

In the last 10-15 years, the Longmont Police Department has made a bigger effort to hire officers who buy into the program. LCJP, according to Cage, has also put in the effort to build strong relationships with the police.

“They are accepted into our culture, which is tough to do. It is tough to break into police culture...They are a part of our police department now,” Cage said.

Cage has spent his career referring cases to restorative justice and now, as a supervisor, advocates for appropriate cases whenever possible.

“To see somebody succeed, to be given a second chance to succeed, is just outstanding. I’ve referred dozens of cases over the years to restorative justice and I have a very good percentage of positive outcomes,” Cage said.

Victims don’t always get to be involved in the process when a case enters the criminal justice system, but according to Cage, victims are more involved in the restorative justice program.

“It’s a way of healing. It is really good for the community because the offender, hopefully, sees the harms that they have done and the victim can see the offender as a person instead of a suspect. I’ve seen people hug at the end of these things,” Cage said.

According to McGoey, police can use their discretion to decide whether the case is a good candidate for restorative justice. She says this decision is typically decided by whether or not the offender is taking responsibility for their actions.

McGoey also said that there have been times when a victim has requested restorative justice in place of charging an offender with a crime.

Over the 25 years of service, LCJP has gone from being able to only serve juveniles with low-level offenses to include adults facing misdemeanor and felony-level charges. McGoey said.

“Most restorative justice in the country is still geared toward youth,” which makes LCJP unique and is a measure of and a record of their success, McGoey said.

Community involvement

McGoey said the program owes its success to the community members, volunteers and police officers who are willing to refer and participate in cases.

“They have participated in and seen that this really does serve victims, gives victims a voice in getting their needs met and helps our community become safer by reducing recidivism, repairing harmed relationships between family members and neighbors and invites people to come together to connect and build relationships in a way that otherwise is not happening,” McGoey said.

LCJP volunteers and clients meet as part of the restorative justice program. (courtesy photo)

LCJP volunteers and clients meet as part of the restorative justice program. (courtesy photo)

Like most social programs, the work of reducing recidivism and crime in a community is ongoing and ever-changing. LCJP recognizes that they need to remain flexible with the community's needs and are currently working on a program that targets juvenile marijuana cases.

“LCJP is really committed to looking, observing, listening to the needs of the community and being responsive so that we can provide a restorative intervention where needed,” McGoey said.

LCJP welcomes the community to participate in the process, taking on the ‘it takes a village mentality.’ Community members are invited to “explore multiple ways of volunteering to support restorative justice,” according to the website.

“We would like to become more of a household name in Longmont. We would like to have more community awareness about what we do here, also for community members to feel really proud about the value in the city of having restorative justice. We invite more engagement and participation across the board. We are always looking for more ways to serve the community with restorative practices,” McGoey said.