This content was originally published by the Longmont Observer and is licensed under a Creative Commons license.

Conversations over Longmont’s Vance Brand Airport are often as dramatic as the mountainous landscape surrounding it.

“Vance Brand is an asset the city has that is not being monetized to the extent that it could be,” City Council Member, Marcia Martin points out. “We are setting out to maximize the utility of the airport without changing it too drastically.”¹

HOW THE AIRPORT OPERATES

Vance Brand Airport (known by its call sign as LMO) currently occupies 262 acres at the westernmost edge of town, housing 124 hangars and accommodating 352 aircraft on average². A whopping 83% of all revenue generated by LMO derives from these privately leased hangars and, as Airport Manager, David Slayter elaborates, the space is maintained “through funding from those revenues and a Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) grant,” with the intent “to be as self-sustaining as possible.” Slayter collects payments himself annually, with “a few paying monthly, a couple quarterly and a few twice a year.”³

These leases run annual rates ranging from $0.36 to $0.94 per square foot and are amongst the most affordable in the state. But because of these low rates (averaging $0.08 below the nationwide market average), LMO generates the second-lowest revenue of all Colorado airports, whose hangars are primarily owned by their respective cities or counties outright2. Though more commercially vested and set amidst wide business sprawl, Rocky Mountain Metro Airport generates an average $460.5 million for Broomfield and Jefferson County compared to the comparably meager $378,955 procured thus far by LMO for Longmont’s economy this year.4,5

The remaining 17% of income generated by LMO is divided between fuel tax refunds and numerous other fees, such as cell tower leases and event space rentals.¹ State grants secured for the airport dropped by a precipitous $13,118 between 2016 and 2017, but Slayter qualifies the dip as dependent upon what projects are proposed for issuance: at times a “reimbursement for a grant may carry from one year into the next dependent upon when the project is completed and payment is made.”6

Slayter, experienced in aviation operations and management, professes that “as a one-person department” – he is the sole, full-time paid employee of LMO – safely maintaining operations is his primary concern. “We try to break even,” he continues, “and we do accept private donations along with funding from the airport fund, not taxpayer dollars.” These funds, he adds, go towards LMO’s maintenance and helps offset costs for sponsorship and events such as public air shows of which $15,453 and $17,191 was privately donated for this year and 2016 respectively.3,6

CITIZEN CONCERNS

Of chief concern to Longmont’s citizens are noise complaints, and no one voice is as invested as Scott Stewart. “The airport didn’t build the town,” says the longtime resident who has become a mainstay at Council and Airport Advisory Board meetings. Noise pollution stemming from pilots not adhering to the city’s Voluntary Noise Abatement Procedures (VNAP, referred colloquially as ‘flying friendly’) “has changed my quality of life,” with Stewart adding his criticisms of such procedures has made him the target of scrutiny.7

Other residents, however, such as Wendy Conder of local Windemere Realty, are rarely bothered by the sound of aircraft. “We’ve lived by the airport for twenty-two years,” she says, “and though the weekends are often busier, especially in the summer, it can be quite charming.” As a real estate broker, Conder readily discloses the airport’s proximity to nearby properties though states that fact is rarely off-putting to potential home buyers. “Many people recognize it as part of the territory,” she adds.8

ADDRESSING CONCERNS

“We can’t regulate noise abatement at all,” David Slayter states, as provenance of such issues is regulated by the FAA which itself does not intervene directly unless dangerous practices or regulatory violations become evident.9

Exemptions or qualifiers to this procedure – like imposing hours of operation or prohibiting the use of certain aircraft – would “create an unmanageable situation,” says City Communications Manager, Marijke Unger, adding it would violate several state and federal laws. “If those things become locally controlled, interstate commerce would be affected along with all sorts of issues – you simply wouldn’t be able to plan,” she concludes.10

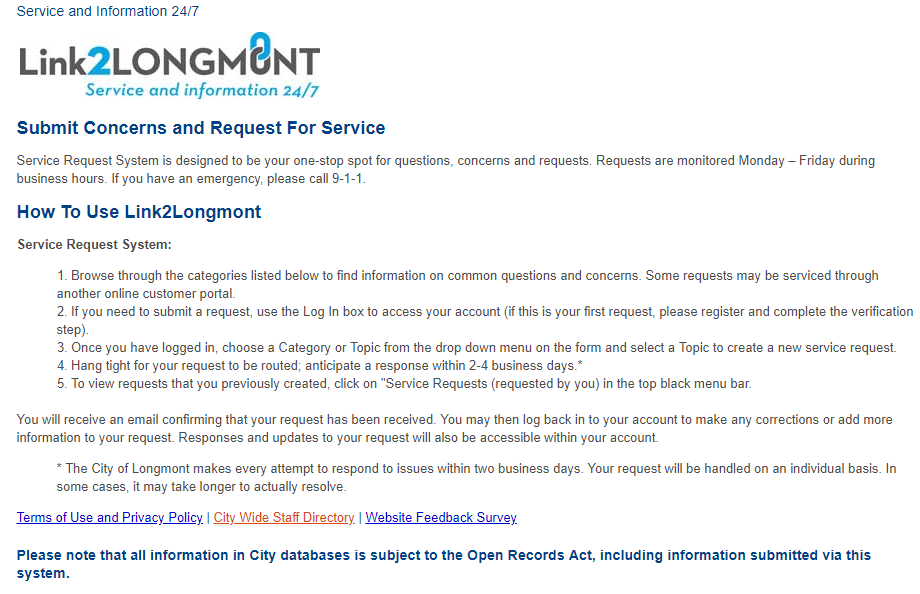

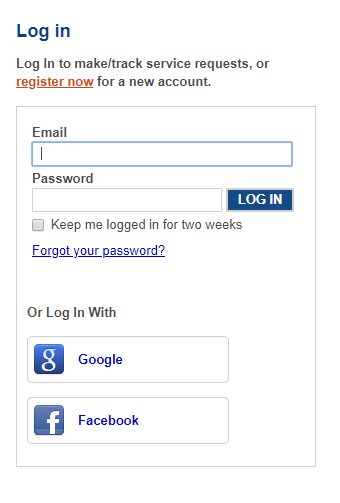

To allow residents to express their views on airport noise “we decided to use the Service Request system the city already had in place,” Slayter adds, which is accessible to the public via the City of Longmont website. Complaints are officially registered via this system enabling Slayter to regularly receive notifications of airport-specific concerns needing to be addressed or resolved: separate classifications exist to compartmentalize noise complaints, safety concerns, technical issues and so on.3 His “one-man show” position, however, does limit how many of these concerns are attended to on a daily basis.

The current web portal allows users to describe the offending aircraft and even upload photos but this itself is not without issue: minutes of a March 8, 2018 Airport Advisory Board meeting reveal Former Board Member, Dan Dolce implored the city to disregard anonymous complaints.11 The current site lacks required fields to input name or address information although citizens must first create a city account to lodge a grievance. Scott Stewart contends this colors the tenor of the city’s interactions with the citizenry, “caring more about them than they care about us.”7 Locals expressing concern, Stewart contends, should not be subject to an ‘enemies list’ hinging upon the disclosure of personal information.

[The reporter tested this complaint procedure on the respective city website and was required to create an account dependent on information for first name, last name, personal phone number and consenting to the city’s terms of service and privacy policies.]

Council Member Martin has suggested the city install an authentication system within the portal to “allow anonymous complaints unless the person chose to supply their name,” but technical complications of incorporating such a system into the preexisting mainframe have prevented it being implemented thus far.12 Martin is deeply aware of this schism, stressing “a lot of constituents I speak with are quite knowledgeable about FAA regulations and various craft,” noting one in particular (a bright purple Twin Otter propeller plane used by on-site Mile-Hi Skydiving) “is the real noisy one.”

[Mile-Hi Skydiving was contacted for this article but did not respond by time of publication.]

Though VNAP enforcement is restricted to an informal ‘honor system’ (Stewart maintains mandatory adherence is both “essential and achievable”),13 Martin speculates LMO opponents “tend to focus on things that might produce a case for closing the airport,” a scenario that could potentially cost millions of dollars at the city’s expense. “If we cannot keep the airport open,” she continues, “we have to pay back those FAA grants and they won’t let us close the airport ‘on-spec’ to see if the land is worth paying back their money.”

PROSPECTIVE PROJECTS

Avenues to remedy opinion against LMO along with invigorating business prospects are being explored by the local Airport Advisory Board, who conducts research and consults City Council on all airport-related issues. This contingent of aviators and business owners shares a wealth of expertise among them, including former City of Denver CFO, Tom Briggs, who helped shepherd Denver International Airport from off the page and into the sky. “Ultimately, the issue is increasing economic opportunity for people. Vance Brand Airport can do more for the people of Longmont,” says Briggs.14

Extending the runway – a Council-approved component of the airport’s master plan currently waiting on local, state and federal funds for completion15 – could prove itself key to LMO’s prosperity. Thirty-nine acres of the airport’s grounds are currently eyed for further commercial development (four acres reserved on the property’s north side, the remainder open south of the runway).2 Briggs notes heightened business activity “is likely to attract better ground services for users,” increasing fuel tax flows to the city (which have steadily declined from 2016 to 2018) and allow companies reliant on jet aircraft to operate from the airport safely.14

Martin states, “Commercial airlines or scheduled flights will not come to Longmont no matter what,” and the city and AAB are exploring quieter jet models to simultaneously stimulate commerce and lessen preexisting complaints.1

“If the temperature is too hot, a jet has to sit and idle on the jetway to burn off enough fuel to take off,” Council Member Martin explains, citing companies like NASA (currently developing prototype craft with Gulfstream III models) are keen to test quiet, energy-efficient aircraft at sites across the country.16 When suggesting LMO as a potential candidate, as Longmont “has good, different atmospheric conditions,” Martin stated the city’s development committee “leapt on the idea,” though any actionable development has yet to be pursued within Longmont or elsewhere in Colorado.

Skepticism of quiet jets, however, abounds: Scott Stewart states the influence zone (the radius of airspace allotted for air traffic patterns) of jets can be significantly larger than of general aviation craft, potentially affecting a greater number of residents.7 Stewart also cites LMO’s light profits as reason enough to dissuade any further local investment, potentially making “an already bad situation even worse.”

Marijke Unger, a pilot herself, acknowledges that while such jets “may be less loud overall and it may take less time to exit the pattern, the frequency of the noise, I would find, more difficult to deal with.”10 She also recognizes that for some, noise from different styles of planes may be upsetting; resulting in a no-win solution for air traffic.

Similar thoughts are echoed by Wade Tagg, personal pilot for Oskar Blues proprietor Dale Katechis. “When you’re climbing faster in a jet, you can notice the noise,” adding, the current model he operates – a Phenom 300 light jet – is demonstrably quieter than the single-engine Pilatus PC-12 turboprop he piloted previously.17 But when pressed for flat-out objectivity, Tagg admits, “a ‘quiet’ jet is really just a ‘less noisy’ jet.” All-electric aircraft yield significant potential to remedy noise pollution but are years away from becoming commonplace at LMO or readily abundant elsewhere throughout Colorado.

Outside addressing noise concerns, Martin also champions a City Charter amendment to extend private leases of the airport’s hangars beyond its current twenty-year cap. “There are many other things that are more important to the city than being restricted to twenty-year leases. In today’s climate, you have to do big projects through public-private partnerships” and “you build things like that with forty or fifty-year financing,” says Martin.¹ However, amending the City Charter requires a vote by Longmont residents, and a concrete proposal by council for an intended 2019 or 2020 ballot initiative is still in its embryonic stages.15

Coupled with David Slayter’s intent to make LMO “the aviation hub for Boulder County” with an emphasis on “working with more energy-efficient companies,” a vision emerges of constructing a homegrown destination for aviation enthusiasts as well as the general public.3

“Dale has had casual discussions about potentially making something work out there,” says Tagg of his boss Katechis (whose restaurant ventures include local favorites Liquids & Solids, CHUBurger and Cyclhops), “but as of now it’s just a nice idea.”17

LMO AND LONGMONT’S COMMUNITY

Ideas, even lucrative ones, must, however, be tethered to facts of supply and demand, says Stewart: “The fact is, they’re not making great money with the leases they already have…because they cater to an aging demographic [that is] often resistant to change,” and asking citizens to invest significant time and money for a grand proposal “is a failure of marketing that over-serves a shrinking minority.”

[When asked for statistics gauging public-private interest in LMO such as car rentals to and from the property or the number of school field trips visiting on-site, neither Vance Brand Airport nor the City of Longmont track or store such records.]

Aviation’s hold on American consciousness is strong, however, as imagery of “pilots as heroes for our country” still resonates even with Stewart himself, “and deservedly so.” Earlier this year the airport hosted, with namesake Astronaut Vance D. Brand at hand, its biannual Airport Expo themed to ‘Planes with a Purpose,’ highlighting its relationships with search and rescue, medical transportation, wildlife protection and several other community enterprises.

The event proved successful with an estimated 7,500 guests in attendance, no surprise to David Slayter, who believes the enthusiastic turn out “speaks volumes to what people think about Vance Brand Airport.”3

“General aviation often suffers from the idea it’s a ‘rich man’s playground,’” Wade Tagg observes, who has twenty-five years prior flight instructor experience under his belt.17 Current costs can be prohibitively expensive for some: not including flight instruction, oil checks and refueling (itself averaging $5.50 per gallon for a standard 42 gallon tank) the most conservative estimate for recreational flying is at least $6,300 a year, not including the aircraft itself which could be rented (as low as $122/hour) or bought ($8,000).18

Trends towards less expensive, smaller, sustainable, and – yes, quieter – electric aircraft, however, would almost certainly democratize the pursuit, Tagg contends.

“There are also many facets not measured or reported,” he continues, “like police assistance or transporting cancer patients to care facilities.” Tagg himself transported an Oskar Blues’ CAN’d Aid envoy to support the delivery of clean drinking water to beleaguered citizens of Flint, Michigan two years ago: He happily recounts the endeavor as a perfect summation of “the type of guy Dale is.” Tagg professes “we were looking at moving operations to Metro about five years ago but Dale ultimately decided to stay in Longmont. It’s our base.”17

On what a 1,000-foot extension of LMO’s runway could mean for future endeavors, Tagg speculates, “Even five hundred or five hundred-fifty feet could open the book,” engendering heightened corporate operations, business traffic and accessibility. That said, he and Katechis are content with Longmont’s airport as it services their needs nicely, “though not everyone works like us,” he states.

TO THE HORIZON

All parties surrounding the functions and fate of the airport agree the Longmont community is instrumental to demonstrating their respective side of the issue. “If some kid goes to those grounds to watch planes take off and that sets them on a career path, that’s a wonderful thing,” Scott Stewart replies. “I would just hope that same kid understands how to respect their community and act responsibly within it.”

“Community engagement is key,” Council Member Martin states, referencing the Airport Expo as proof the Advisory Board “has a lot to work with” moving forward. “When people visit Longmont and realize what a lovely little town it is – authentic, charming – we should be able to accommodate where we’re going without sacrificing what we are.”

At times steadied and sometimes turbulent, debate over Vance Brand Airport is likely to continue. Active involvement, critical analysis and even casual interest could be integral to navigating this issue as is keeping one’s eyes – and ears – trained to the sky.

SOURCES

- Conversation with Marcia Martin, City Council Member

- Vance Brand Airport Business Plan

- Conversation with David Slayter, Manager, Vance Brand Airport

- Email correspondence with Paul Anslow, Manager, RMM Airport, Broomfield

- Lucienne Petrocco, CORA Requests (Reference No.196, 200, 201)

- Email correspondence with David Slayter, Manager, Vance Brand Airport

- Conversation with Scott Stewart, Resident

- Conversation with Wendy Conder, Resident

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Website – Noise Emissions

- Conversation with Marijke Unger, City Communications Manager

- City of Longmont Public Records Portal – Council Notes (3/8/2018)

- Email correspondence with Marcia Martin, City Council Member

- City of Longmont – Voluntary Noise Abatement Procedures

- Email correspondence with Tom Briggs, Airport Advisory Board Member

- Email correspondence with Rigo Leal, City Public Information Officer

- Stewart, Jack. “NASA Tests A Plane That is Very, Very Quiet,” Wired.Com, July 7, 2018

- Conversation with Wade Tagg, Personal Pilot, Oskar Blues

- Buehler, Nathan. “Economics of Owning a Small Plane,” Investopedia, October 13, 2018

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)