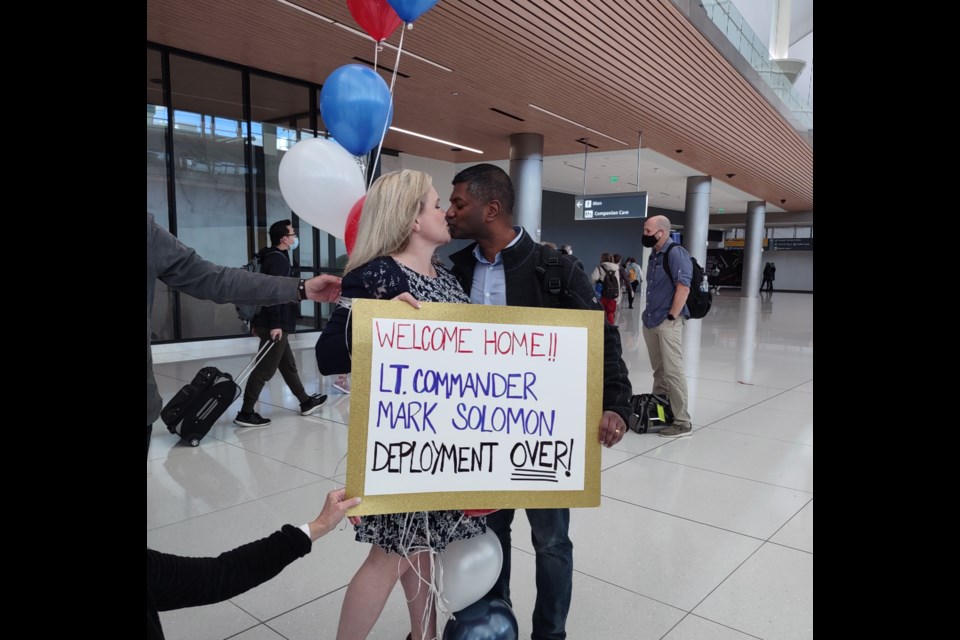

Mark Solomon, co-founder of Veterans Community Project, or VCP, knows first hand the struggles veterans have integrating back into their communities. After a year coordinating military intelligence in east Africa, Solomon returned home in time for the holidays.

Solomon, a Navy reservist and intelligence officer, returned from his second deployment to the waiting arms of family, loved ones and VCP colleagues at Denver International Airport. The reunion included an honor guard from the Patriot Guard Riders and members of the Veterans of Foreign Wars.

Solomon said the turnout at the airport was outstanding and all the hugs were amazing, but reintegration and transitioning back to civilian life will be a bit of a struggle for him. Though this current deployment was for just under a year, Solomon said coming home still meant finding his place in a family that lived without him.

“I’m lucky my people are well-adjusted. My wife is awesome and spectacular and unwilling to put up with crap raising two teenagers,” Solomon said.

Both Solomon and his wife, Chasity, laughed about it a little, along with the role-reversal of Solomon’s experience as a commanding officer while on active duty.

“It’s good to have him home, but it’s a little weird. Reentry is always odd,” Chasity Solomon said. “He’s been away bossing people in the military and now he’s home and has to get used to being bossed around by me.”

Solomon likened the return home to a sort of amnesia and feeling slightly out of sync especially with some of the simplest things.

Solomon’s youngest son, Nicholas, started high school while he was in Africa. With high school starting an hour earlier than middle school, Solomon said he had a moment of confusion when his son asked for a ride to school, not remembering the schedule change.

Even going to cook dinner, Solomon experienced a moment of displacement as he hunted through cabinets for an herb blend he remembered being there a year ago. It took a moment to remember it hadn’t been moved but used while he was gone, he said.

Though Solomon’s memory of home may have felt paused to him while he was away, life marched on for his wife and sons. To keep up with Nicholas Solomon’s professional football aspirations, Chasity Solomon spent time in the yard snapping footballs and playing tackle dummy, she said.

Those missed moments followed Solomon on both deployments, he said. During his first deployment, he said he missed his youngest son’s first steps while his wife ran the household. Even now, both Mark and Chasity Solomon agreed that their sons struggled a little, adjusting to having their dad home as another parental authority in the house.

“It’s not just the service member that makes the sacrifice, there’s a lot of people that have to do this. There are families left behind,” Solomon said. “I know a lot of single moms and dads at home with screaming kids, just waiting for their spouse to come home.”

Solomon was grateful to be home with his supporting family who understood his experience, but recognized that not all veterans had that sort of support system. The need to support those who served was one of the motivating factors in why he and five of his friends and fellow combat veterans started VCP.

“Having that sort of baseline is where we came at this (VCP), we all have that shared experience of deploying and coming back,” Solomon said. “We realized that we have brothers and sisters out there who are struggling and we needed to do something about it.”

VCP didn’t want to replicate or overlap the work that other veterans support organizations were doing, he said. The goal was to fill in the gaps where other veteran-focused nonprofits couldn’t help, or where bureaucracy prevented those veterans from getting help.

Helping veterans figure out the resources and pathways through bureaucracy is part of the goal of VCP, Solomon said. In his own career as a reservist with the Navy, Solomon recognized some of the issues presented in gaining access to veteran services. If Solomon hadn’t received active duty orders a few years into his commission, it would take six years of reserve enlistment to qualify for veteran benefits. If a reservist were injured before that six years, they may not qualify for those benefits.

“These are the things that create loopholes and issues where we decided that if someone needs help and they served, if they were willing to put their lives on the line to serve this country, we would honor that commitment with a commitment of our own,” Solomon said.

Solomon gave the example of a veteran who had deployed four times in the Middle East before getting discharged for driving drunk, explaining how that veteran would be unable to receive benefits from Veterans Affairs or other support organizations due to his dishonorable discharge status.

“If that vet needs something or has issues, the answer is typically ‘sorry, can’t help you,’ from these organizations, not because they’re bad just because he doesn’t qualify for those services,” Solomon said. “That’s the sort of thing where we realized there are a lot of people that fall into those loopholes.”

Now that he’s home and getting used to civilian life again, Solomon said his next goal is to find the best way to help VCP in Longmont and the other branches. Visiting Longmont’s new VCP Outreach Center and the build site for the Veteran Village are top priorities, as well as supporting the staff through fundraising and storytelling.

“What is spectacular to me about these people is that they ... have this mindset where they won’t sit around and wait when there is work to be done,” Solomon said.

If you or someone you know has a journey to share please email the Leader at [email protected].